|

|||

The Hinterkaifeck Murders and the Devil’s Footprints

Source :http://armchairdetective.wordpress.com/2009/11/23/hinterkaifeck/

The 1922 murders of Hinterkaifeck are one of Germany´s most mysterious unsolved murder cases. Hinterkaifeck was the name of a small farmstead outside Groebern, between the Bavarian towns of Ingolstadt and Schrobenhausen (approximately 70 km north of Munich). Here, farmer Andreas Gruber (63) lived with his wife Cäzilia (72) and their widowed daughter Viktoria Gabriel (35) – the official owner of the farm – and her two children Cäzilia (7) and Josef (2). The family was rather well-off and well-regarded, though not exactly well-liked. They are said to have kept mostly to themselves. Gruber in particular is described as a brutish, sullen loner. He is said to have beaten and mistreated his children, of whom only Viktoria survived. His daughter Viktoria was a popular member of the church choir, known for her beautiful voice. It was common knowledge that Gruber had an incestuous relationship with his daughter (something which, while illegal, was not infrequent in rural areas at the time), and actively prevented her from marrying again. His wife apparently suffered from the knowledge, but did little to stop things. A schoolmate of young Cäzilia´s reported in 1984 that Cäzilia was reproached for falling asleep in school on the 31st and related that the night before, there had been a severe argument in the family and her grandmother had stormed out of the house wanting to kill herself. They had searched for her for hours. (Earlier, in 1951, the same witness had stated that it had been Viktoria who they had searched for).  Even though a neighboring farmer, Lorenz S., had officially admitted to being the father of little Josef, it was rumored that the boy was in fact the fruit of the incestuous relationship between his mother and grandfather. Schlittenbauer was not the only local lad who claimed to have been with Viktoria.

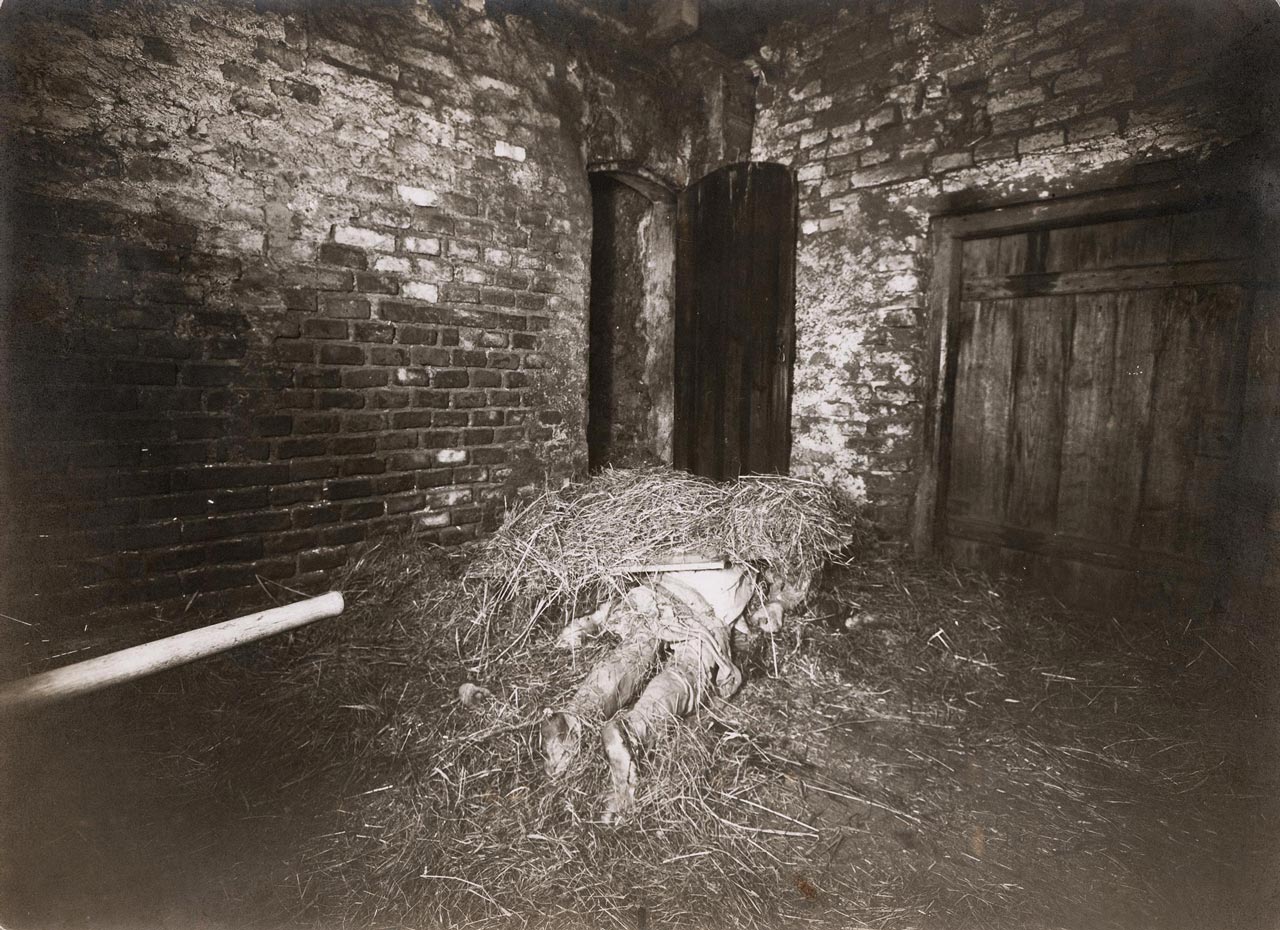

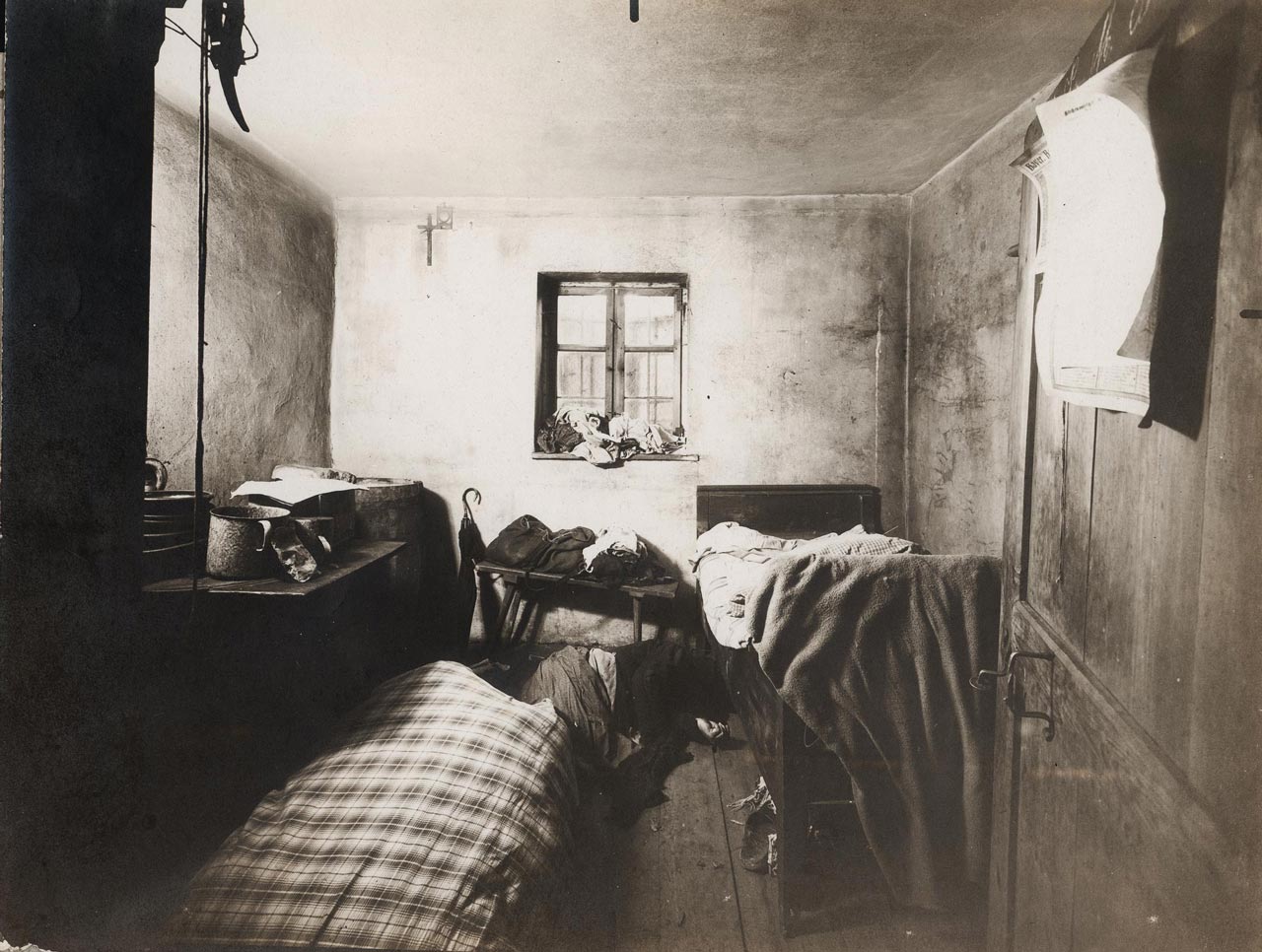

On the following Tuesday, the 4th of April, some neighbours went to the farmstead because none of the inhabitants had been seen for several days, which was rather unusual. The postman had noticed that the mail from the previous Saturday was still where he had left it. Furthermore, young Cäzilia had not turned up for school on Monday, nor had she been there on Saturday. The family also had been absent from church on Sunday, which was unusual, given Viktoria´s position in the choir. Inspector Georg Reingruber and his colleagues from the Munich Police Department made immense efforts investigating the killings. More than 100 suspects have been questioned through the years, but to no avail. The most recent questioning took place in 1986, but even that was fruitless. In 2007 the students of the Polizeifachhochschule (Police Academy) in Fürstenfeldbruck got the task to investigate the case once more with modern techniques of criminal investigation. Their final report is kept secret. To this day, many hobby investigators continue to investigate the case. The day after the discovery, on the 5th of April, court physician Dr. Johann Baptist Aumüller performed the autopsies in the barn. It was established that a pickaxe was the most likely murder weapon. The corpses were beheaded, and the skulls sent to Munich, where clairvoyants examined them without result. The autopsy also showed that the younger Cäzilia had been alive for several hours after the assault. Lying in the straw, next to the bodies of her grandparents and her mother, she had torn her hair out in tufts. The skulls were never actually returned to the bodies and the entire family has been buried without heads. The traces of the skulls have been lost in history. They very likely were destroyed when the forensic department in Nuremberg burned down during WWII. The motive The police first suspected the motive to be robbery, and interrogated several inhabitants from the surrounding villages, as well as travelling craftsmen and vagrants. The robbery theory was, however, abandoned when a large amount of money was found in the house. Only the paper money was gone, while considerable amounts of gold coins and valuables had been left. It is believed that the perpetrator(s) remained at the farm for several days – someone had fed the cattle, and eaten food in the kitchen: the neighbours had also seen smoke from the chimney during the weekend – and anyone looking for money would have found it. But why, if they were not looking for money, would the perpetrators stay there for so long and keep up the appearance that someone was alive? Whoever did this obviously had some farmers knowledge, and also a farmers´ mind: They did not harm any of the animals, not even the dog (until the very last day) though it must have been a hazard. The use of the pickaxe as the murder weapon also points towards this: The victims had been hit with precision and a lot of hatred, their heads had been split but their bodies had apparently not been hit. Whoever did this must have been familiar enough with using a pickaxe to do so without thinking.  Whoever did this also must have been known on the farm, as the Grubers´ dog – a Pomeranian, said to be a keen watchdog – was first heard inside the house, but and later seen tied up and healthy, barking like crazy outside the barn by a mechanic who came to the farm on Monday. The dog was found inside the barn, hurt and frightened, by the men who discovered the dead on Tuesday. So the killer was familiar enough to the dog to be able to handle it during the three days he stayed on the farm after the murders. All of the corpses had been covered. Viktoria, her daughter and her parents had been placed on top of each other in the barn and covered with a door, which in turn was covered with some hay. The maid had been covered with her own bedcloth and little Josef was covered with one of Viktoria´s skirts. This points towards the fact that the killer(s) had some emotional connection to the victims. By covering them up, they tried to hide what they had done, so they did not have to face it. At some point, the death of Karl Gabriel, Viktoria’s husband who had been reported killed in the French trenches in 1914, was called into question. His body had never been found and two people claimed to have encountered a German-speaking Russian officer after WWII, who claimed to be “the Hinterkaifeck killer”. A former friend of Karl´s also claimed to have met him in the 1920s. These accounts have been proven wrong and the death of Karl Gabriel seems ascertained enough to discount this theory. Apart from that, Karl Gabriel had planned to leave Viktoria even before going to the war, in 1914. He might have faked his death to be free of her, although this would have been very difficult for a young farmers´ boy in 1914 to accomplish, but why would he return 7 years later and kill the whole family, including young Cäzilia, his own daughter? From the position of the bodies and their condition, Viktoria was probably the first to die. She was strangled as well as slain, and she was still dressed, as was her mother, whereas Andreas Gruber and little Cäzilia were already in night garb. It is thought that Viktoria was the first to encounter her killer, probably let him in. Maybe an argument erupted (what went on in the barn couldn´t be heard from the living quarters so it wouldn´t have alarmed the others all at once), the first murder happened and led to a killing spree – out of resentment, but also to do away anyone who might know he was there? Many of those who study this case consider little Josef the key to it all. Why kill him, too? Maybe because he knew and recognized the killer? At two years, he would have been able to say something like “uncle xxx was here”, even if he might not have understood everything else that went on. When little Josef was born, Viktoria claimed for Lorenz S. to be the father. He denied it and reported Viktoria and her father to the police for incest. On Viktoria´s request, probably garnished with the hint of a chance to marry the wealthy widow, S. withdrew his report later and confirmed to be the father. He had to pay an alimony of several thousand marks to the Grubers, which Viktoria gave him. With this down payment, it was agreed that he was free of any responsibility and Andreas Gruber was made the child´s guardian. In fact, this kind of deal was illegal even then, and a recent TV documentary on the case revealed that apparentlyshortly before she was killed, Viktoria planned to sue Schlittenbauer for alimony payments. According to one source, Andreas Gruber was said to have been waiting for an important letter, though we do not know what that letter was supposed to contain, nor who it was from, or even if this was indeed the case. If the killer was waiting for a letter to arrive (and, presumably, destroy) it would at least explain why he stayed on the farm for days after the murder. But if the letter was in connection with Viktoria´s alimony suit, wouldn´t the lawyer have come forth? After all, the murders made the headlines all over the country.

Lorenz S. had remarried at that point. His first child with his new wife had died and been buried only a few days before the murder. Did the notion of having to pay for a child that he couldn´t be sure was his while his own child had not lived trigger something terrible…? S. was obviously familiar with the Grubers´ farmstead. He was one of the men who went to investigate after the family had not been seen for days and discovered the corpses in the barn. He had apparently no problem handling them, pulling those lying on top of each other apart. The other two told him not to disturb anything but he said he had to make sure where “his boy” was. According to one of the other two men, S. “disturbed everything there was to disturb” and displayed a surprising familiarity with the farm: He went into the house from the barn (both buildings were interconnected) and unlocked the front door from the inside. (Was the key in the lock or was he in possession of the key that had been missed days before?) He knew that the door to the maid´s room had to be opened in an unusal way, by lifting the handle instead of pressing it down. But if he had been the perpetrator, he would have spent the previous days on the farm and would have had enough time to cover his tracks. He would have had no need to mess with the crime site. S. stayed on the farm until the police arrived, feeding the cattle. He even had a meal there himself. Just like the unknown perpetrator, he was apparently not disturbed by the presence of the corpses. Even though people were a bit more familiar with death and dead people back then, the other two men were rather shaky seeing the slain victims. On the other hand, he might have acted “on auto-pilot” in a state of emergency/shock, like someone who is witness to a severe accident and calmly does everything that needs to be done, shock not setting in until much later. In spite of his apparent worry about “his boy”, he does not seem to have minded the decease of the family a lot: Years later, he said during an interrogation that the Lord had his hand in the right place when this happened, these were bad people. He did not exclude the two children. The dog behaved in an unusual way towards S. when they found the corpses. He stayed in his vicinity and barked at him. S. claimed this was because he had gotten blood from the corpses on his shoes. S. had no alibi for the night of the murders. According to his family, he spent the night at their barn to watch out for burglars after having heard of Gruber´s findings. But S. was suffering from asthma, so how likely is it for him to have slept in the barn? On the other hand, how likely is it for him to slay six people in a very short time? S. lived only 350 metres away from Hinterkaifeck, so he could have easily gone over there and back without his absence being noticed. And years later, when the murders were discussed in the local pub, S. repeatedly talked in the first person when speculating about how the killer may have gone about and referred to him as “I”. While some of S.´s behaviour makes him look suspicious, a lot of open questions remain. And S. is by no means the only suspect. To this day, a lot has been speculated about, but no killer has been identified for certain, nothing has been proven. And so the Hinterkaifeck murders leave us with many questions. Source comments powered by Disqus Submit News/Videos/Links | Discuss article | Article Link | More Unsolved and Unexplained Mysteries |

More can be addded on request. Direct your requests at vinit@theunexplainedmysteries.com