Battle of Los Angeles

|

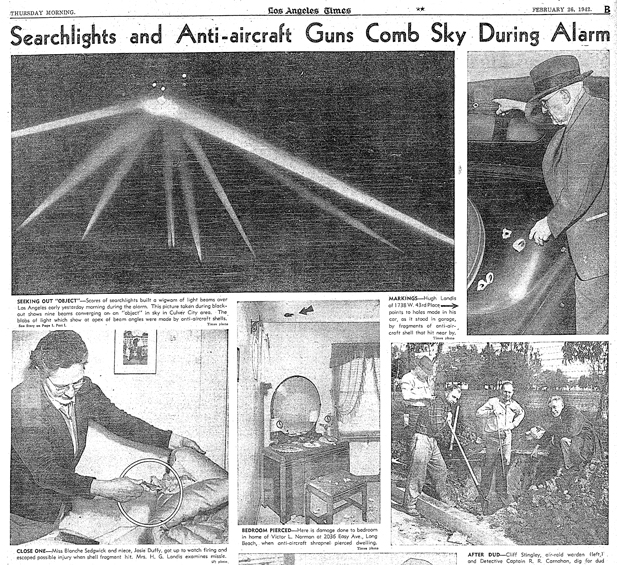

The Battle of Los Angeles is the name given by contemporary news agencies to a sighting of one or more unidentified flying objects which took place from late February 24 to early February 25, 1942 in which eyewitness reports of an unknown object or objects over Los Angeles, California, triggered a massive anti-aircraft artillery barrage. The Los Angeles incident occurred less than three months after America's entry into World War II as a result of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Initially the target of the aerial barrage was thought to be an attacking force from Japan, but it was later suggested to be imaginary and a case of "war nerves", a lost weather balloon, a blimp, a Japanese fire balloon or psychological warfare technique, staged for the benefit of coastal industrial sites, or even an extraterrestrial aircraft. The true nature of the object or objects remains unknown.

|

Alarms raised

Prior to the incident in Los Angeles, the Ellwood shelling, in which the Japanese submarine I-17 surfaced and fired on an oil production facility near Santa Barbara, had occurred on February 23, 1942. Reports indicated that afterwards the submarine was heading south, the general direction of Los Angeles.

Unidentified objects were reported over Los Angeles during the night of February 24 and the early morning hours of February 25, 1942. Air raid sirens were sounded throughout Los Angeles County at 2:25 a.m. and a total blackout was ordered. Thousands of air raid wardens were summoned to their positions.

At 3:16 a.m. on February 25, the 37th Coast Artillery Brigade began firing 12.8-pound anti-aircraft shells into the air at the object(s); over 1400 shells would eventually be fired . Pilots of the 4th Interceptor Command were alerted but their aircraft remained grounded. The artillery fire continued sporadically until 4:14 a.m. The objects were said to have taken about 20 minutes to have moved from over Santa Monica to above Long Beach. The "all clear" was sounded and the blackout order lifted at 7:21 a.m.

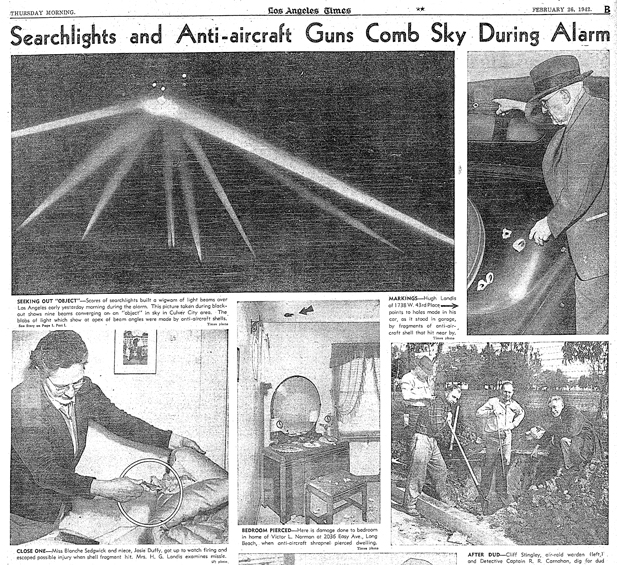

In addition to several buildings damaged by friendly fire, three civilians were killed by the anti-aircraft fire, and another three died of heart attacks attributed to the stress of the hour-long bombardment.

The incident was front-page news along the U.S. Pacific coast, and earned some mass media coverage throughout the nation. One Los Angeles Herald Express writer who observed some of the incident insisted that several anti-aircraft shells had struck one of the objects, and he was stunned that the object had not been downed. Reporter Bill Henry of the Los Angeles Times wrote , "I was far enough away to see an object without being able to identify it ... I would be willing to bet what shekels I have that there were a number of direct hits scored on the object."

Editor Peter Jenkins of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner reported, "I could clearly see the V formation of about 25 silvery planes overhead moving slowly across the sky toward Long Beach." Long Beach Police Chief J.H. McClelland said "I watched what was described as the second wave of planes from atop the seven-story Long Beach City Hall. I did not see any planes but the younger men with me said they could. An experienced Navy observer with powerful Carl Zeiss binoculars said he counted nine planes in the cone of the searchlight. He said they were silver in color. The group passed along from one battery of searchlights to another, and under fire from the anti-aircraft guns, flew from the direction of Redondo Beach and Inglewood on the land side of Fort MacArthur, and continued toward Santa Ana and Huntington Beach. Anti-aircraft fire was so heavy we could not hear the motors of the planes."

Identification elusive

Aside from unidentified airplanes, proposed explanations of the event then and now have included misidentification of weather balloons, sky lanterns, and Japanese fire balloons or blimps.

However, in the case of Japanese fire balloons (a proposal from later decades), they did not even exist in 1942. Some witnesses said the object caught in the searchlights was moving too slowly to have been a plane and there was common speculation in the newspapers that it was some type of balloon, such as a weather balloon or a Japanese blimp. Various problems noted with such explanations included the fact that many witnesses reported sighting multiple objects, not a single weather balloon or blimp, some moving at much faster aircraft speed, and the extreme unlikelihood that any balloon-like object could have survived such a massive bombardment. American balloon experts also opined it unlikely that the Japanese would use blimps since they had no fireproof helium to fill them and a blimp filled with explosive hydrogen gas would be even more unlikely to survive. In any case, no debris from the purported object or objects was ever reported on the ground following the bombardment.

Since some high government officials such as Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall and Secretary of War Henry Stimson (see below) declared real aircraft to be involved, yet no satisfactory explanation was ever forthcoming, some Ufologists in the present day feel the incident should be treated as an early and true UFO sighting, much like the so-called foo fighters later reported during the war by Allied and Axis flight crews.

Official response

Within hours of the end of the air raid (February 25), Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox held a press conference and opined that the entire incident was a "false alarm" due to anxiety and "war nerves". Many in the press doubted this explanation, some suspecting a cover up. An editorial in the Long Beach Independent wrote, "There is a mysterious reticence about the whole affair and it appears that some form of censorship is trying to halt discussion on the matter."

Knox's comments quickly brought a defensive response from the Army that there definitely were flying aircraft and the battle was for real. The following day (February 26) Secretary of War Stimson backed them up. Citing a report from the Army Chief of Staff (Gen. Marshall--see next section), Stimson said there may have been as many as 15 aircraft involved, some flying very slowly and others up to 200 miles an hour.

Stimson then commented that, "It seems reasonable to conclude that if unidentified airplanes were involved, they may be some from commercial sources, operated by enemy agents for the purpose of spreading alarm, disclosing location of anti-aircraft positions, or the effectiveness of blackouts."

Speculation was then rampant as to where airplanes could have been based. Theories ran from a secret base in northern Mexico to Japanese submarines stationed offshore with the capability of carrying planes.

Others speculated that the incident was either staged or exaggerated to give coastal defense industries an excuse to move further inland. In fact, Secretary Knox, after declaring it was a false alarm, added that vital defense industries in southern California might have to be moved inland because of enemy activity along the coast. This provoked an acid front page editorial from the Los Angeles Times: "The reasoning is at least extraordinary. If there were no planes and no danger, wherein does this particular incident in any way support the theory that our great aircraft industry should be moved inland. Is it supposed to be damaged by false alarms and jittery nerves on the part of others? ...Least comprehensible of all is what the Navy head sees in the case to abet the desire of some government officials and some inland communities to transfer Coastal industries to the latter."

The sharply conflicting statements from government and military officials as to what actually happened, plus lack of adequate explanation, brought other harsh criticism in newspaper editorials. In particular, if there truly was nothing to the incident, the possibility that Army personnel had fired heavy artillery shells for nearly an hour at nothing at all — killing three civilians in the process — led some critics to suggest that the U.S. Army officers in charge were dangerously incompetent.

Some Congressmen also demanded answers. For example, Representative Leland Ford of Santa Monica wanted a Congressional investigation. He was quoted stating, "...none of the explanations so far offered removed the episode from the category of 'complete mystification' ... this was either a practice raid, or a raid to throw a scare into 2,000,000 people, or a mistaken identity raid, or a raid to lay a political foundation to take away Southern California's war industries."

In the end, however, there was no Congressional investigation; it was never clearly established whether there were objects in the sky, or what their origin may have been if they did exist.

Liked it ? Want to share it ? Social Bookmarking

Discuss article |

Article Link

|

More unsolved mysteries on Unexplained Mysteries

|