|

|||

Meet Homo Naledi: New species of human ancestor discovered

Source : http://www.cnn.com/2015/09/10/africa/homo-naledi-human-relative-species/index.html

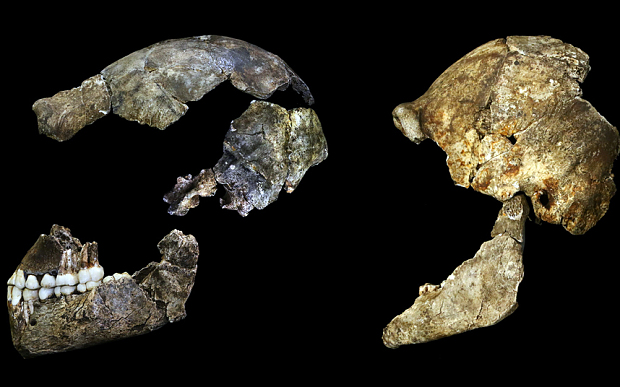

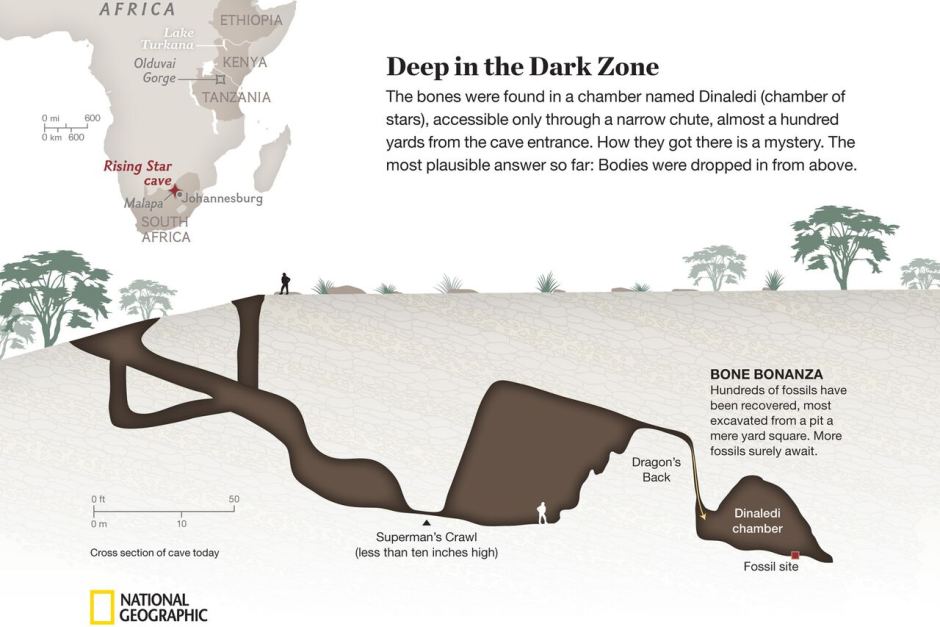

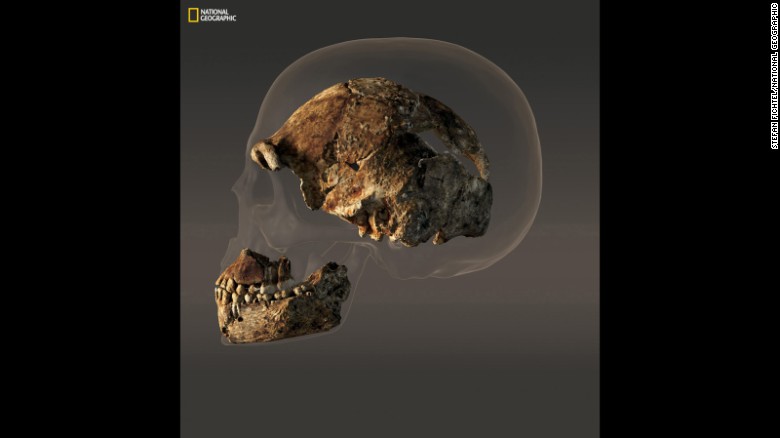

A huge haul of bones found in a small, dark chamber at the back of a cave in South Africa may be the remnants of a new species of ancient human relative. Scientists find fossils of our ancient relative, who had surprisingly human-like features, in a remote cave near Johannesburg Explorers discovered the bones after squeezing through a fissure high in the rear wall of the Rising Star cave, 50km from Johannesburg, before descending down a long, narrow chute to the chamber floor 40 metres beneath the surface. The entrance chute into the Dinaledi chamber is so tight - a mere eight inches wide - that six lightly built female researchers were brought in to excavate the bones. Footage from their cameras was beamed along 3.5km of optic cable to a command centre above ground as they worked inside the cramped enclosure.  The excavators recovered more than 1,500 pieces of bone belonging to at least 15 individuals. The remains appear to be infants, juveniles and one very old adult. Thousands more pieces of bone are still in the chamber, smothered in the soft dirt that covers the ground. The leaders of the National Geographic-funded project believe the bones - as yet undated - represent a new species of ancient human relative. They have named the creature Homo naledi, where naledi means “star” in Sesotho, one of the official languages of South Africa, and the primary official language of Lesotho. But other experts on human origins say the claim is unjustified, at least on the evidence gathered so far. The bones, they argue, look strikingly similar to those of early Homo erectus, a forerunner of modern humans who wandered southern Africa 1.5m years ago.

When an amateur caver and university geologist arrived at Lee Berger's house one night in late 2013 with a fragment of a fossil jawbone in hand, they broke out the beers and called National Geographic. Berger, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, had unearthed some major finds before. But he knew he had something big on his hands. What he didn't know at the time is that it would shake up our understanding of the progress of human evolution and even pose new questions about our identity.  Two years after they were tipped off by cavers plumbing the depths of the limestone tunnels in the Rising Star Cave outside Johannesburg, Berger and his team have discovered what they say is a new addition to our family tree. The team is calling this new species of human relative "Homo naledi," and they say it appears to have buried its dead -- a behavior scientists previously thought was limited to humans.  Berger's team came up with the startling theory just days after reaching the place where the fossils -- consisting of infants, children, adults and elderly individuals -- were found, in a previously isolated chamber within the cave. The team believes that the chamber, located 30 meters underground in the Cradle of Humanity world heritage site, was a burial ground -- and that Homo naledi could have used fire to light the way. "There is no damage from predators, there is no sign of a catastrophe. We had to come to the inevitable conclusion that Homo naledi, a non-human species of hominid, was deliberately disposing of its dead in that dark chamber. Why, we don't know," Berger told CNN.  "Until the moment of discovery of 'naledi,' I would have probably said to you that it was our defining character. The idea of burial of the dead or ritualized body disposal is something utterly uniquely human." Standing at the entrance to the cave this week, Berger said: "We have just encountered another species that perhaps thought about its own mortality, and went to great risk and effort to dispose of its dead in a deep, remote, chamber right behind us." "It absolutely questions what makes us human. And I don't think we know anymore what does." The first undisputed human burial dates to some 100,000 years ago, but because Berger's team hasn't yet been able to date naledi's fossils, they aren't clear how significant their theory is. Berger tried to put the new find into perspective. "This is like opening up Tutankhamen's tomb," he said. "It is that extreme and perhaps that influential in this stage of our history."  Homo naledi is a strange mosaic of the ancient and the thoroughly modern. Naledi's brain was no bigger than an orange, scientists say. Its hands are superficially human-like, but the finger bones are locked into a curve -- a trait that suggests climbing and tool-using capabilities. Homo naledi was relatively big: it stood about 5 feet tall, had long legs, and its feet are almost identical to ours, suggesting it had the ability to walk long distances. "Overall, Homo naledi looks like one of the most primitive members of our genus, but it also has some surprisingly human-like features, enough to warrant placing it in the genus Homo," says John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a senior author on the papers describing the new species that were published Thursday.  The scientists can make these claims, in part, because of the sheer scale of the find. In the vault at the University of Witwatersrand, hundreds of priceless specimens lie in padded cases across the room. So far they've unearthed more than 1,500 fossil remains in total -- the largest single hominin find yet revealed on the continent of Africa, the cradle of human evolution.

comments powered by Disqus Submit News/Videos/Links | Discuss article | Article Link More Unsolved and Unexplained Mysteries |

More can be addded on request. Direct your requests at vinit@theunexplainedmysteries.com