| |

Unexplained Mysteries - Lost giants of Australia rediscovered |

|

Source : http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/features/subterranean-secrets-of-our-lost-giants/story-e6frg6z6-1225814209439

|

|

AS you drive from Perth down to your favourite Margaret River winery, you'll pass close to the place where palaeontologist Gavin Prideaux and his team from Adelaide's Flinders University are brushing and scraping their way towards scientific discovery.

You won't notice them, though. They're deep below the surface in a network of secret caves known to only a handful of people. Small openings lead into vast limestone caverns filled with dazzling stalagmites and stalactites.

But it's not these stunning formations the scientists have come to see.

They're here to look at very old bones, the bones of Australia's large beasts that disappeared thousands of years ago.

These creatures were big. Wombats as big your fridge lying on its side, kangaroos standing more than 2m tall, a goanna called Megalania that could eat you for lunch, and a very nasty piece of work called Thylacoleo carnifex or the marsupial lion.

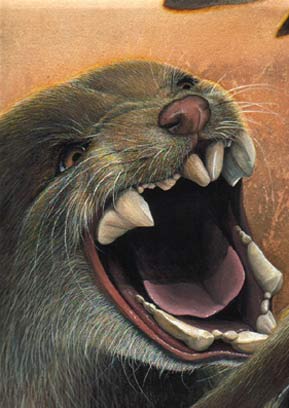

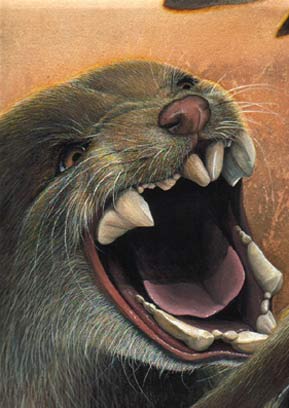

Built like a leopard on steroids, Thylacoleo was the apex carnivore in the group. He could easily make a meal of most others by dropping from trees and stabbing them in the neck with his huge front teeth, then slicing them open with his razor-sharp thumb claw.

This group of beasts is known as Australia's megafauna and they walked this land for at least a million years.

Scientists have been picking up their bones for more than a century. Perhaps the most exciting find was a complete Thylacoleo skeleton discovered deep in a remote cave on the Nullarbor in 2002. At the time, this set of bones created quite a stir within the world scientific community.

About 400,000 years earlier the unfortunate creature fell into the cavern through a small hole. Unable to climb out, it wandered aimlessly until it died. As time passed the animal's flesh melted away leaving a complete set of bones. For palaeontologists, who normally measure their finds in fragments of bone, this was the holy grail of Thylacoleo skeletons.

For years a debate has raged over how and when our megafauna became extinct.

Was a climatic event responsible? Did something happen to their food source or did disease sweep across the country and wipe them out? Perhaps they were hunted to extinction.

In the northern hemisphere, mammoth remains have been found with the scars of hunting, but no Australian megafauna bones have shown evidence of being killed by humans.

In the Margaret River cave, Prideaux is slowly removing fragments of bone from layers of sediment.

If you have a mental picture of palaeontologists as dull scientists with long beards hunched over microscopes, let me set you straight. Beards are a common theme, but that's where the stereotype ends.

I join Prideaux on his dig for two days and learn quickly there are parts of a palaeontologist's life more akin to an extreme sportsman than a laboratory boffin.

My first challenge is climbing down to where the team is working. Tight Entrance Cave, as one of these holes is known, is aptly named. You can walk within touching distance of its mouth and be unaware of it.

Picture a roundish rock chimney with an assortment of jagged protrusions around its sides disappearing into the ground in front of you. It's about 7m deep and just a little wider than the average human body.

"Just hang on to the rope and jam your body against the wall as you go down, and always make sure you've got at least one foot and one hand well anchored before you make your next move; we don't want any accidents," the scientists tell me. That is just the first part of the climb, and I am well bruised and scratched by the time I drop into the small ante-room at the bottom.

From there we crawl into a tunnel that is just big enough to squeeze through if you suck in your stomach and hold your breath. With my face centimetres from the dirt, I am starting to realise why the other guys are wearing dust masks.

It is pitch black by this time, too, of course.

We all have helmets with torches mounted on them that spread a small pool of light ahead of us, but all I can see are the soles of the boots crawling in front of me. After a while it gets wider and we can even stand.

Almost down and there is just one last tricky manoeuvre: the human bridge.

This is where we straddle a crevasse by jamming our back against one wall, then stretching our legs across to the wall on the other side.

Below us is a drop of several metres into a tight wedge of rock. The trick is to shuffle horizontally across to a small ledge, then drop on to flat ground.

Read more at http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/features/subterranean-secrets-of-our-lost-giants/story-e6frg6z6-1225814209439

Liked it ? Want to share it ? Social Bookmarking

Discuss article |

Article Link

|

More unsolved mysteries on Unexplained Mysteries

|