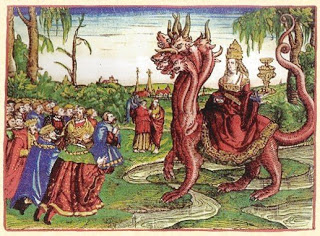

Pope Joan OR Popess Joan – Mysterious Woman Pope

According to legend, Pope Joan was a woman who concealed her gender and ruled as pope for two years, from 853-855 ad. Her identity was exposed when, riding one day from St. Peter’s to the Lateran, she stopped by the side of the road and, to the astonishment of everyone, gave birth to a child.

Pope Joan was a legendary female Pope who allegedly reigned for a few years some time during the Middle Ages. The story first appeared in 13th-century chronicles, and was subsequently spread and embellished throughout Europe. It was widely believed for centuries, though modern religious scholars consider it fictitious, perhaps deriving from historicized folklore regarding Roman monuments or from anti-papal satire.

The first mention of the female pope appears in the chronicle of Jean de Mailly, but the most popular and influential version was that interpolated into Martin of Troppau’s Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum, later in the 13th century. Most versions of her story describe her as a talented and learned woman who disguises herself as a man, often at the behest of a lover. In the most common accounts, due to her abilities, she rises through the church hierarchy, eventually being elected pope. However, while riding on horseback, she gives birth, thus exposing her gender. In most versions, she dies shortly after, either being killed by an angry mob or from natural causes. Her memory is then shunned by her successors.

The story is as enduring as it is dubious: A millennium or so ago in Rome, the pope was riding in a procession when suddenly shethat’s right, shewent into labor and had a baby.

Nonsense? Europeans in the Middle Ages didn’t think so. The story of a pope named Joan, writes historian J.N.D. Kelly in his Oxford Dictionary of Popes, “was accepted without question in Catholic circles for centuries.” Only after the Reformation, when Protestants used the story to poke fun at Roman Catholics, did the Vatican begin to deny that one of its Holy Fathers had become an unholy mother.

The tale faded in the 17th century but never died. While most Americans apparently have never heard of the story, it continues to fascinate people in Europe. In the last three years, 2 million Germansand about 100,000 Americanshave bought copies of Pope Joan, a historical novel by Donna Woolfolk Cross, a New York writer who suggests that a 400-year clerical coverup kept her hero from being recognized as one of history’s most famous women. Legions of Americans likely will become believers, too, if Hollywood’s Harry Ufland, producer of The Last Temptation of Christ and Snow Falling on Cedars, shoots the Pope Joan movie he hopes to make next year.

During the Middle Ages, many versions of the “popess” affair appeared. Most accounts came from friars compiling church histories, though the Vatican later would argue that Protestant forgers tinkered with the text. A few medieval chronicles said Joan’s great deception occurred in the 10th or 11th century. The report that gained the widest acceptance, written in 1265 by a Dominican friar from Poland named Martin of Troppau, set the unblessed event in the ninth century.

Papal momma. According to most versions, spectators watched in horror as the pope, trying to mount a horse, went into labor and gave birth to a son. Moments later, some reports said, the crowd tied her feet to the horse’s tail, then stoned her to death as she was dragged along a street. Still other records showed her banished to a convent and living in penance as her son rose to become a bishop.

The female pope reportedly was born in Germany of English missionary parents and grew up unusually bright in an era when learned women were considered unnatural and dangerous. To break the glass ceiling, it was said, she pretended to be male. At 12, she was taken in masculine attire to Athens by a “learned man,” a monk described as her teacher and lover.

Disguised in the sexless garb of a cleric, she “made such progress in various sciences,” Martin of Troppau wrote, “that there was nobody equal to her.” Eventually, it was said, she became a cardinal in Rome, where her knowledge of the scriptures led to her election as Pope John Anglicus. Martin of Troppau’s account had her ruling male-dominated Christendom from 855 till 858, specifically two years, seven months, and four days. Her original name, according to some, was Agnes. Others called her Gilberta and Jutta. Many years after she diedassuming she ever livedscribes began calling her Joan, the feminine form of John.

But by no name would she win a place in the Vatican’s official catalog of popes. The church insists that its papal line, dating back to St. Peter, is an unbroken string of men. Scholars tend to agree. An array of reference books, from the Encyclopaedia Britannica to the Oxford Dictionary of Popes, dismiss Pope Joan as a mythical or legendary figure, no more real than Paul Bunyan or Old King Cole. (Another Joan, the 15th-century martyr Joan of Arc, is honored by the church as a saint.)

The chief weakness of the Pope Joan story is the absence of any contemporary evidence of a female pope during the dates suggested for her reign. In each instance, clerical records show someone else holding the papacy and doing deeds that are transcribed in church history.

Another problem is the gap between the alleged event and the news of it. Not until the 13th century400 years after Joan, by the most accepted accounts, ruleddoes any mention of a female pope appear in any documents. That’s akin to word breaking out just now that England in 1600 had a queen named Elizabeth.

The historical gap, some Joanites suggest, was deliberately created. Cross, the novelist, argues that clerics of the day were so appalled by Joan’s trickery that they went to great lengths to avoid and eliminate any written report of it.

The main arguments against the legend? That there are no records from the time of the supposed Popess about any such incident. And that there are no gaps in the historical record that would allow for an otherwise undocumented Pope to have held office.

There’s even a theory that the name of a street in Rome, the Vicus Papissa, named for a woman of the Pape family, gave rise to the story of a procession of a female Pope through that street, interrupted by her sudden, quick and quite public labor.

I know that there are those who disagree with my conclusion about Pope Joan. Because it’s true that much of women’s history has been lost or suppressed through negligence, it’s easy to accept a theory about a missing female Pope. But just because there is no evidence doesn’t make it true. Believable evidence is simply not there, and the “evidence” presented is easily explained. Until there’s different evidence that builds a stronger case, this is one women’s history story that I don’t accept.

Actually, in history, the main purpose of the story of the female Pope was not to testify to the possibilities for women, beyond the ordinary, as were many legends of warrior women and women leaders that were based on verifiable truths or germs of truth. The purpose of the story of the woman Pope was originally as a lesson: that such roles were improper for women and that women who took on such roles would be punished. Later, the story was used to discredit the Roman Catholic Church and the authority of the Pope, by showing how fallible the church could be in making such a horrible error. Imagine, not even noticing that a woman was leading the Church! Patently ridiculous! was the conclusion expected of anyone hearing the story.

Not exactly a way to promote positive role models for women.

In 1856, the Encyclopedia Britannica took on the Pope Joan legend, and concluded that the legend was false. Here’s an excerpt from the article there:

The grounds on which this conclusion is arrived at may be briefly stated. In the first place, 200 years elapsed between the era of the supposed pope and the date at which her name is first mentioned by any historian. In the next place there were at Rome, during the time assigned to her Papacy four persons, who each in succession sat on the papal throne, and left behind them many and various writings. Had they ever heard of the story, it is impossible to believe that they should each and all have passed it over in silence as they have done. In the third place, all the contemporary writers, without a single exception, attest that, immediately on the death of Leo IV., the papal chair was offered and accepted by Benedict III.

At the same time, though the story of Pope Joan is given up by all historians alike as a fable, it is impossible that it should have found believers and upholders for so many centuries had there been nothing in the annals of the church to give a sort of colour to it. Many conjectures have been advanced upon the subject, of which by far the most plausible is that of Biancho-Giovini, who proves clearly enough that the papal chair was often virtually occupied by a woman. Pope John X., elected in 914, owed his elevation entirely to his mistress Theodora, whose beauty, talents, and intrigues had made her mistress of Rome about the beginning of the tenth century. At a late period Theodora’s daughter, Marozia, wielded a similar influence over Sergius III., and finally raised her son by that pope to the pontifical throne, with the title of John XI. At a still later period, John XII. was so completely governed by one of his concubines, Raineria by name, that he entrusted to her much of the administration of the holy see. These, and other instances of the same kind that might be adduced, account satisfactorily enough for the origin of the fable of Pope Joan.

Source : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Joan