Cottingley Fairies – Hoax or Real ?

In 1920 a series of photos of fairies captured the attention of the world. The Cottingley Fairies photos had been taken by two young girls, the cousins Frances Griffith and Elsie Wright, while playing in the garden of Elsie’s Cottingley village home. Photographic experts examined the pictures and declared them genuine. Spiritualists promoted them as proof of the existence of supernatural creatures, and despite criticism by skeptics, the pictures became among the most widely recognized photos in the world. It was only decades later, in the late 1970s, that the photos were definitively debunked.

The Cottingley Fairies appear in a series of five photographs taken by Elsie Wright (1901–88) and Frances Griffiths (1907–86), two young cousins who lived in Cottingley, near Bradford in England. In 1917, when the first two photographs were taken, Elsie was 16 years old and Frances was 9. The pictures came to the attention of writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who used them to illustrate an article on fairies he had been commissioned to write for the Christmas 1920 edition of The Strand Magazine. Doyle, as a spiritualist, was enthusiastic about the photographs, and interpreted them as clear and visible evidence of psychic phenomena. Public reaction was mixed; some accepted the images as genuine, but others believed they had been faked.

Interest in the Cottingley Fairies gradually declined after 1921. Both girls married and lived abroad for a time after they grew up, yet the photographs continued to hold the public imagination. In 1966 a reporter from the Daily Express newspaper traced Elsie, who had by then returned to the UK. Elsie left open the possibility that she believed she had photographed her thoughts, and the media once again became interested in the story.

In the early 1980s Elsie and Frances admitted that the photographs were faked, using cardboard cutouts of fairies copied from a popular children’s book of the time, but Frances maintained that the fifth and final photograph was genuine. The photographs and two of the cameras used are on display in the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, England.

During World War I, ten-year-old Frances Griffiths, who was from South Africa, moved into the English home of her aunt and uncle, the Wrights, while her father fought in the war. She and her cousin, thirteen-year-old Elsie, often played together in the large garden of the family’s Cottingley village home.

In July 1917 the pair asked to borrow the camera of Elsie’s father, telling him they wanted to take a photo of the fairies they had been playing with all morning. Elsie’s father laughingly agreed and showed them how to use the camera. An hour later the girls returned, declaring their project a success. And when Mr. Wright developed the plate that evening, he could see that there did indeed appear to be a fairy posing with Frances in the photo. However, he dismissed the girls’ explanation, assuming the picture was some kind of trick. He asked Elsie why there appeared to be “bits of paper” in the photo.

Even when the girls took a second photo a little over a month later, showing Elsie with a gnome, the father treated the images as a joke and filed them away.

However, Elsie’s mother, Polly Wright, had a stronger belief in the supernatural, and was more intrigued by the photos. In 1919 she attended a lecture on spiritualism and following it, she showed the photos to the speaker, asking him if they “might be true after all.” The speaker brought the photos to the attention of Edward Gardner, a leader of the Theosophical movement, who in turn asked a photographer, Harold Snelling, to examine them. Snelling declared the photos were “genuine unfaked photographs of single exposure, open-air work, show movement in all the fairy figures, and there is no trace whatever of studio work involving card or paper models, dark backgrounds, painted figures, etc.”

Once they had received this stamp of approval, the fairy images began circulating throughout the British spiritualist community, and soon came to the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries. Doyle was a passionate believer in spiritualism, and he latched onto the images, convinced they were conclusive photographic proof of the existence of supernatural fairy beings.

At Doyle’s urging, the girls took three more pictures of fairies in August 1920. Doyle then wrote an article about the photographs that appeared in the December 1920 issue of The Strand Magazine, in which he passionately argued for the authenticity of the images. This article brought the photos to the attention of the wider public and sparked an international controversy that pitted spiritualists against skeptics.

Initial examinations

Gardner sent the prints along with the original glass-plate negatives to Harold Snelling, a photography expert. Snelling’s opinion was that “the two negatives are entirely genuine, unfaked photographs … [with] no trace whatsoever of studio work involving card or paper models”. He did not go so far as to say that the photographs showed fairies, stating only that “these are straight forward photographs of whatever was in front of the camera at the time”. Gardner had the prints “clarified” by Snelling, and new negatives produced, “more conducive to printing”, for use in the illustrated lectures he gave around the UK. Snelling supplied the photographic prints which were available for sale at Gardner’s lectures.

Author and prominent spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle learned of the photographs from the editor of the spiritualist publication Light. Doyle had been commissioned by The Strand Magazine to write an article on fairies for their Christmas issue, and the fairy photographs “must have seemed like a godsend” according to broadcaster and historian Magnus Magnusson. Doyle contacted Gardner in June 1920 to determine the background to the photographs, and wrote to Elsie and her father to request permission from the latter to use the prints in his article. Arthur Wright was “obviously impressed” that Doyle was involved, and gave his permission for publication, but he refused payment on the grounds that, if genuine, the images should not be “soiled” by money.

Gardner and Doyle sought a second expert opinion from the photographic company Kodak. Several of the company’s technicians examined the enhanced prints, and although they agreed with Snelling that the pictures “showed no signs of being faked”, they concluded that “this could not be taken as conclusive evidence … that they were authentic photographs of fairies”. Kodak declined to issue a certificate of authenticity. Gardner believed that the Kodak technicians might not have examined the photographs entirely objectively, observing that one had commented “after all, as fairies couldn’t be true, the photographs must have been faked somehow”. The prints were also examined by another photographic company, Ilford, who reported unequivocally that there was “some evidence of faking”. Gardner and Doyle, perhaps rather optimistically, interpreted the results of the three expert evaluations as two in favour of the photographs’ authenticity and one against.

Doyle also showed the photographs to the physicist and pioneering psychical researcher Sir Oliver Lodge, who believed the photographs to be fake. He suggested that a troupe of dancers had masqueraded as fairies, and expressed doubt as to their “distinctly ‘Parisienne'” hairstyles

Skeptics noticed many problems with the photos, in addition to the obvious one that the fairies look like bits of paper. For instance, in the first photo why is Frances not looking at the fairies? (The girls claimed they were so used to the fairies that they often paid them no attention.) And why does the second fairy from the left not have wings? In the second photo, why is Elsie’s hand bizarrely elongated? (Frances attributed this to “camera slant.”) In the fourth photo, why is the fairy dressed in the latest French fashions?

Despite these problems, the photos continued to attract believers. Much of this belief might be attributed to the context of the times. By the end of World War One the English were emotionally bruised and battered by four years of unrelenting bloodshed. They seemed to be in need of something that would reaffirm their belief in goodness and innocence. They found this reaffirmation in the fairy photographs of Frances and Elsie.

Debunked

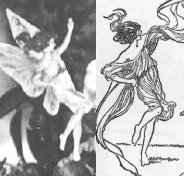

It was not until 1978 that James Randi pointed out that the fairies in the pictures were very similar to figures in a children’s book called Princess Mary’s Gift Book, which had been published in 1915 shortly before the girls took the photographs.

Subsequently, in 1981, Elsie Wright confessed to Joe Cooper, who interviewed her for The Unexplained magazine, that the fairies were, in fact, paper cutouts. She explained that she had sketched the fairies using Princess Mary’s Gift Book as inspiration. She had then made paper cutouts from these sketches, which she held in place with hatpins. In the second photo (of Elsie and the gnome) the tip of a hatpin can actually be seen in the middle of the creature. Doyle had seen this dot, but interpreted it as the creature’s belly button, leading him to argue that fairies give birth just like humans!

Below is a side-by-side comparison of the figures in Princess Mary’s Gift Book and the fairies in the first Cottingley fairy photo.

In 1983, the cousins admitted in an article published in the magazine The Unexplained that the photographs had been faked, although both maintained that they really had seen fairies. Elsie had copied illustrations of dancing girls from a popular children’s book of the time, Princess Mary’s Gift Book, published in 1914, and drew wings on them. They said they had then cut out the cardboard figures and supported them with hatpins, disposing of their props in the beck once the photograph had been taken. But the cousins disagreed about the fifth and final photograph, which Doyle in his The Coming of the Fairies described in this way:

Seated on the upper left hand edge with wing well displayed is an undraped fairy apparently considering whether it is time to get up. An earlier riser of more mature age is seen on the right possessing abundant hair and wonderful wings. Her slightly denser body can be glimpsed within her fairy dress.