The Tarim Mummies – The Deads Tell a Tale

Source : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarim_mummies

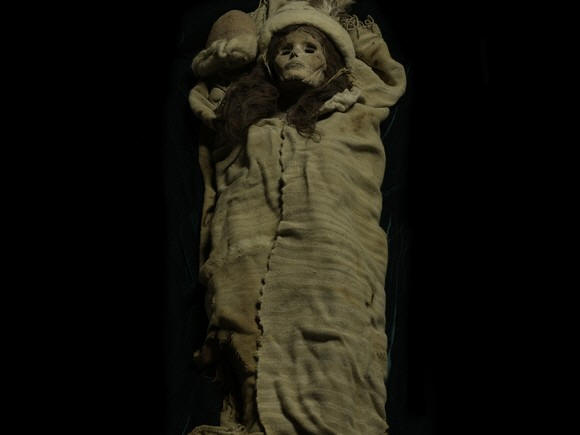

The Tarim mummies are a series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang, China, which date from 1900 BC to 200 AD. In addition to being very well-preserved finds, controversy flows around them as DNA tests seem to show that they are the result of Asian and Caucasian mating thousands of years before it’s commonly thought that the two peoples intermingled.

The Taklamakan Mummies (Tocharian mummies)

In the late 1980’s, perfectly preserved 3000-year-old mummies began appearing in a remote Taklamakan desert. They had long reddish-blond hair, European features and didn’t appear to be the ancestors of modern-day Chinese people. Archaeologists now think they may have been the citizens of an ancient civilization that existed at the crossroads between China and Europe.

Victor Mair, a specialist in the ancient corpses and co-author of Mummies of the Tarim Basin, said:”Modern DNA and ancient DNA show that Uighurs, Kazaks, Krygyzs, the peoples of Central Asia are all mixed Caucasian and East Asian. The modern and ancient DNA tell the same story. The discoveries in the 1980s of the undisturbed 4,000-year-old Beauty of Loulan and the younger 3,000-year-old body of the Charchan Man are legendary in world archaeological circles for the fine state of their preservation and for the wealth of knowledge they bring to modern research. In the second millennium BC, the oldest mummies, like the Loulan Beauty, were the earliest settlers in the Tarim Basin.

Archeological record

At the beginning of the 20th century European explorers such as Sven Hedin, Albert von Le Coq and Sir Aurel Stein all recounted their discoveries of desiccated bodies in their search for antiquities in Central Asia. Since then many other mummies have been found and analysed, most of them now displayed in the museums of Xinjiang. Most of these mummies were found on the eastern (around the area of Lopnur, Subeshi near Turfan, Kroran, Kumul) and southern (Khotan, Niya, Qiemo) edge of the Tarim Basin.

The earliest Tarim mummies, found at Qäwrighul and dated to 1800 BCE, are of a Caucasoid physical type whose closest affiliation is to the Bronze Age populations of southern Siberia, Kazakhstan, Central Asia, and the Lower Volga.The cemetery at Yanbulaq contained 29 mummies which date from 1100500 BCE, 21 of which are Mongoloidthe earliest Mongoloid mummies found in the Tarim basinand 8 of which are of the same Caucasoid physical type found at Qäwrighul.

Notable mummies are the tall, red-haired “Chärchän man” or the “Ur-David” (1000 BCE); his son (1000 BCE), a small 1-year-old baby with blond hair protruding from under a red and blue felt cap, and blue stones in place of the eyes; the “Hami Mummy” (c. 1400800 BCE), a “red-headed beauty” found in Qizilchoqa; and the “Witches of Subeshi” (4th or 3rd century BCE), who wore two foot long black felt conical hats with a flat brim. Also found at Subeshi was a man with traces of a surgical operation on his neck; the incision is sewn up with sutures made of horsehair. Surgery was considered heretical in ancient Chinese medical tradition.

Many of the mummies have been found in very good condition, owing to the dryness of the desert and the desiccation of the corpses it induced. The mummies share many typical Caucasoid body features (elongated bodies, angular faces, recessed eyes), and many of them have their hair physically intact, ranging in color from blond to red to deep brown, and generally long, curly and braided. It is not known whether their hair has been bleached by internment in salt. Their costumes, and especially textiles, may indicate a common origin with Indo-European neolithic clothing techniques or a common low-level textile technology. Chärchän man wore a red twill tunic and tartan leggings. Textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber, who examined the tartan-style cloth, claims it can be traced back to Anatolia, the Caucasus and the steppe area north of the Black Sea.

But the real shock came when Mair looked closely at their faces. In contrast to most central Asian peoples, these corpses had obvious Caucasian, or European, features–blond hair, long noses, deep-set eyes, and long skulls. “I was thunderstruck,” Mair recalls. “Even though I was supposed to be leading a tour group, I just couldn’t leave that room. The questions kept nagging at me: Who were these people? How did they get out here at such an early date?”

The corpses Mair saw that day were just a few of more than 100 dug up by Chinese archeologists over the past 16 years. All of them are astonishingly well preserved. They come from four major burial sites scattered between the arid foothills of the Tian Shan (“Celestial Mountains”) in northwest China and the fringes of the Taklimakan Desert, some 150 miles due south. All together, these bodies, dating from about 2000 B.C. to 300 B.C., constitute a significant addition to the world’s catalog of prehistoric mummies. Unlike the roughly contemporaneous mummies of ancient Egypt, the Xinjiang mummies were not rulers or nobles; they were not interred in pyramids or other such monuments, nor were they subjected to deliberate mummification procedures. They were preserved merely by being buried in the parched, stony desert, where daytime temperatures often soar over 100 degrees. In the heat the bodies were quickly dried, with facial hair, skin, and other tissues remaining largely intact.

Any answers to these questions will most likely fuel a wide- ranging debate about the role outsiders played in the rise of Chinese civilization. As far back as the second century B.C., Chinese texts refer to alien peoples called the Yuezhi and the Wusun, who lived on China’s far western borders; the texts make it clear that these people were regarded as troublesome “barbarians.” Until recently, scholars have tended to downplay evidence of any early trade or contact between China and the West, regarding the development of Chinese civilization as an essentially homegrown affair sealed off from outside influences; indeed, this view is still extremely congenial to the present Chinese regime. Yet some archeologists have begun to argue that these supposed barbarians might have been responsible for introducing into China such basic items as the wheel and the first metal objects. Exactly who these central Asian outsiders might have been, however–what language they spoke and where they came from–is a puzzle. No wonder, then, that scholars see the discovery of the blond mummies as a sensational new clue.

Although Mair was intrigued by the mummies, the political climate of the late 1980s (the Tiananmen Square massacre occurred in 1989) guaranteed that any approach to Chinese archeological authorities would be fraught with difficulties. So he laid the riddle to one side as he returned to his main area of study, the translation and analysis of ancient Chinese texts. Then, in September 1991, the discovery of the 5,000-year-old “Ice Man” in the Alps electrified the world press. The frozen body is thought to be that of a late Neolithic trader, apparently caught by a storm while hiking at an altitude of 10,500 feet. Photos of the Ice Man’s corpse, dried by the wind and then buried by a glacier, reminded Mair of the desiccated mummies in the Ürümqi museum. And he couldn’t help wondering whether some of the scientific detective methods now being applied to the Ice Man, including DNA analysis of the preserved tissue, could help solve the riddle of Xinjiang.

With China having become more receptive to outside scholars, Mair decided to launch a collaborative investigation with Chinese scientists. He contacted Xinjiang’s leading archeologist, Wang Binghua, who had found the first of the mummies in 1978. Before Wang’s work in the region, evidence of early settlements was virtually unknown. In the late 1970s, though, Wang had begun a systematic search for ancient sites in the northeast corner of Xinjiang Province. “He knew that ancient peoples would have located their settlements along a stream to have a reliable source of water,” says Mair. As he followed one such stream from its source in the Tian Shan, says Mair, “Wang would ask the local inhabitants whether they had ever found any broken bowls, wooden artifacts, or the like. Finally one older man told him of a place locals called Qizilchoqa, or ‘Red Hillock.’ ”

It was here that the first mummies were unearthed. This was also the first site visited last summer by Mair and his collaborator, Paolo Francalacci, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Sassari in Italy. Reaching Qizilchoqa involved a long, arduous drive east from Ürümqi. For a day and a half Mair, Wang, and their colleagues bounced inside four- wheel-drive Land Cruisers across rock-strewn dirt roads from one oasis to the next. Part of their journey eastward followed China’s Silk Road, the ancient trade route that evolved in the second century B.C. and connected China to the West. Finally they reached the village of Wupu; goats scattered as the vehicles edged their way through the back streets. Next to the village was a broad green ravine, and after the researchers had maneuvered their way into it, the sandy slope of the Red Hillock suddenly became visible.

“It wasn’t much to look at,” Mair recalls, “about 20 acres on a gentle hill ringed by barbed wire. There’s a brick work shed where tools are stored and the visiting archeologists sleep. But you could spot the shallow depressions in the sand where the graves were.” As Mair watched, Wang’s team began digging up several previously excavated corpses that had been reburied for lack of adequate storage facilities at the Ürümqi museum. Mair didn’t have to wait long; just a couple of feet below the sand, the archeologists came across rush matting and wooden logs covering a burial chamber lined with mud bricks. Mair was surprised by the appearance of the logs: they looked as if they had just been chopped down. Then the first mummy emerged from the roughly six-foot-deep pit. For Mair the moment was nearly as charged with emotion as that first encounter in the museum. “When you’re standing right next to these bodies, as well preserved as they are, you feel a sense of personal closeness to them,” he says. “It’s almost supernatural–you feel that somehow life persists even though you’re looking at a dried-out corpse.”

Mair and Francalacci spent the day examining the corpses, with Francalacci taking tissue samples to identify the genetic origins of the corpses. “He took small samples from unexposed areas of the bodies,” says Mair, “usually from the inner thighs or underarms. We also took a few bones, usually pieces of rib that were easy to break off, since bone tends to preserve the DNA better than muscle tissue or skin.” Francalacci wore a face mask and rubber gloves to avoid contaminating the samples with any skin flakes that would contain his own DNA. The samples were placed in collection jars, sealed, and labeled; Mair made a photographic and written record of the collection.

However, Wang and his colleagues have found some strange, if not aristocratic, objects in the course of their investigations in Xinjiang. At a site near the town of Subashi, 310 miles west of Qizilchoqa, that dates to about the fifth century B.C., they unearthed a woman wearing a two-foot- long black felt peaked hat with a flat brim. Though modern Westerners may find it tempting to identify the hat as the headgear of a witch, there is evidence that pointed hats were widely worn by both women and men in some central Asian tribes. For instance, around 520 B.C., the Persian king Darius recorded a victory over the “Sakas of the pointed hats”; also, in 1970 in Kazakhstan, just over China’s western border, the grave of a man from around the same period yielded a two-foot-tall conical hat studded with magnificent gold-leaf decorations. The Subashi woman’s formidable headgear, then, might be an ethnic badge or a symbol of prestige and influence.

Subashi lies a good distance from Qizilchoqa, and its site is at least seven centuries younger, yet the bodies and their clothing are strikingly similar. In addition to the “witch’s hat,” clothing found there included fur coats and leather mittens; the Subashi women also held bags containing small knives and herbs, probably for use as medicines. A typical Subashi man, said by the Chinese team to be at least 55 years old, was found lying next to the corpse of a woman in a shallow burial chamber. He wore a sheepskin coat, felt hat, and long sheepskin boots fastened at the crotch with a belt.

Another Subashi man has traces of a surgical operation on his neck; the incision is sewn up with sutures made of horsehair. Mair was particularly struck by this discovery because he knew of a Chinese text from the third century A.D. describing the life of Huatuo, a doctor whose exceptional skills were said to have included the extraction and repair of diseased organs. The text also claims that before surgery, patients drank a mixture of wine and an anesthetizing powder that was possibly derived from opium. Huatuo’s story is all the more remarkable in that the notion of surgery was heretical to ancient Chinese medical tradition, which taught that good health depended on the balance and flow of natural forces throughout the body. Mair wonders if the Huatuo legend might relate to some lost Asian medical tradition practiced by the Xinjiang people. One clue is that the name Huatuo is uncommon in China and seems close to the Sanskrit word for medicine.

Another hint of outside connections struck Mair as he roamed across Qizilchoqa. Crossing an unexcavated grave, he stumbled upon an exposed piece of wood, which he quickly realized had once belonged to a wagon wheel. The wheel was made in a simple but distinctive way, by doweling together three carved, parallel wooden planks. This style of wheel is significant: wagons with nearly identical wheels are known from the grassy plains of the Ukraine from as far back as 3000 B.C.

A number of artifacts recovered from the Xinjiang burials provide important evidence for early horse riding. Qizilchoqa yielded a wooden bit and leather reins, a horse whip consisting of a single strip of leather attached to a wooden handle, and a wooden cheekpiece with leather straps. This last object was decorated with an image of the sun that was probably religious in nature and that was also found tattooed on some of the mummies. And at Subashi, archeologists discovered a padded leather saddle of exquisite workmanship.

Could the Xinjiang people have belonged to a mobile, horse-riding culture that spread from the plains of eastern Europe? Does this explain their European appearance? If so, could they have been speaking an ancient forerunner of modern European, Indian, and Iranian languages? Though the idea is highly speculative, a number of archeologists and linguists think the spread of Indo-European languages may be linked to the gradual spread of horse-riding and horse-drawn-vehicle technology from its origins in Europe 6,000 years ago. The Xinjiang mummies may help confirm these speculations.

Perhaps a highly distinctive language would help explain why the Xinjiang people’s distinctive appearance and culture persisted over so many centuries. Eventually they might well have assimilated with the local population–the major ethnic group in the area today, the Uygur, includes people with unusually fair hair and complexions. That possibility will soon be investigated when Mair, Francalacci, and their Chinese colleagues compare DNA from ancient mummy tissue with blood and hair samples from local people.

Besides the riddle of their identity, there is also the question of what these fair-haired people were doing in a remote desert oasis. Probably never wealthy enough to own chariots, they nevertheless had wagons and well-tailored clothes. Were they mere goat and sheep farmers? Or did they profit from or even control prehistoric trade along the route that later became the Silk Road? If so, they probably helped spread the first wheels and certain metalworking skills into China.

Unfortunately, economics dictates that answers will be slow in coming. The Chinese have little money to spare for this work, and Wang and his team continue to operate on a shoestring. Currently most of the corpses and artifacts are stored in a damp, crowded basement room at the Institute of Archeology in Ürümqi, in conditions that threaten their continued preservation. If Mair’s plans for a museum can be financed with Western help, perhaps the mummies can be moved. Then, finally, they’ll receive the study and attention that will ultimately unlock their secrets.

Discuss article