Mysteries of India – Erotic Temples of Khajuraho

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khajuraho

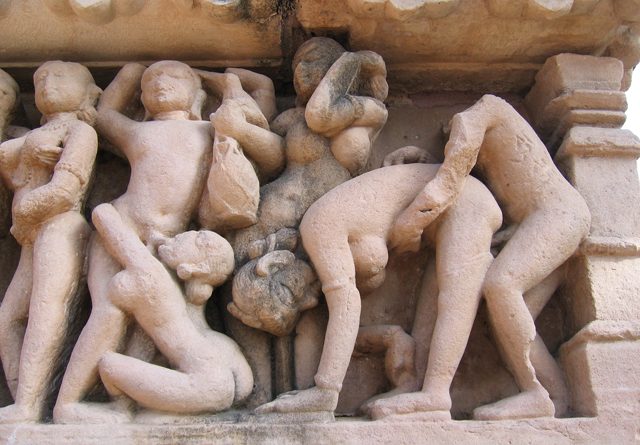

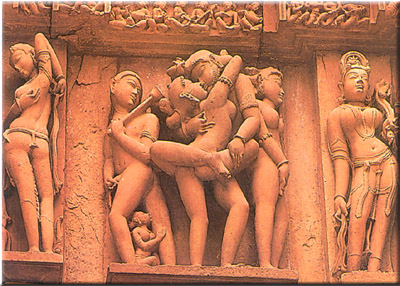

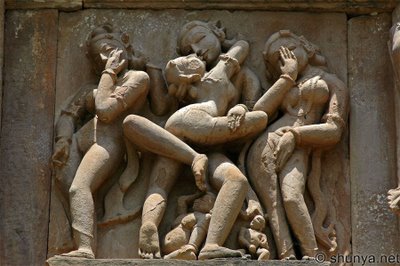

As in the wall sculptures of the Orissan temples, eroticism is a recurrent theme in the shrines at Khajuraho. Various theories have been advanced to account for this, but the commonly accepted explanation is that the many erotic groups depicted here with such abandon represent, the mithuna ritual of the Tantric cult, according to which personal salvation can be attained only through experience: both sensual and spiritual. Another belief is that, being a powerful human experience signifying complete fulfillment through union, the sexual experience here symbolizes the fusion of the individual with the divine. Yet another theory holds that since such sculptures are usually found on the exterior surfaces of a temple and are absent from the interior, it may be concluded that they are meant to test the devotion of the worshipper or to warn him against entering the sanctum until he has conquered carnal desire. Whatever the significance of these sculptures may be, it is fairly clear from their intrinsic artistic merit that the sculptors who fashioned them found the temple walls an easy canvas for the depiction of such an elemental theme as love between man and woman.

A UNESCO world heritage site in central India, Khajuraho is a famous tourist and archaeological site known for its sculptured temples dedicated to Shiva, Vishnu, and Jain patriarchs. Khajuraho was one of the capitals of the Chandela kings, who from the 9th to the 11th century CE developed a large realm, which at its height included almost all of what is now Madhya Pradesh state. Khajuraho extended over 21 sq. km and contained about 85 temples built by multiple rulers from about 950 to 1050. In the late 11th century the Chandela, in a period of chaos and decline, moved to hill forts elsewhere. Khajuraho continued its religious importance until the 14th century (Ibn Batuta was impressed by it) but was afterwards largely forgotten; its remoteness probably saved it from the desecration that Muslim conquerors generally inflicted on Hindu monuments. In 1838 a British army captain, TS Burt, employed by the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, came upon information that led him to the rediscovery of the complex of temples in the jungle in Khajuraho.

Of the 85 original temples-most constructed of hard river sandstone-about 20 are still reasonably well preserved. Both internally and externally the temples are richly carved with excellent sculptures that are frequently sensual and, at times, sexually explicit.

The temples are divided into three complexes-the western is the largest and best known, containing the magnificent Shaivite temple Kandariya Mahadev, a 31m high agglomeration of porches and turrets culminating in a spire. Modern Khajuraho is a small village, serving the tourist trade with hotels and an airport. Khajuraho’s name derives from the prevalence of khajur, or date palms, in the area.

The creators of Khajuraho claimed descent from the moon. The legend that describes the origin of this great dynasty is a fascinating one : Hemavati, the beautiful young daughter of a Brahmin priest was seduced by the moon god while bathing in the Rati one evening. The child born of this union between a mortal and a god was a son, Chandravarman. Harassed by society, the unwed mother sought refuge in the dense forest of Central India where she was both mother and guru to her young son. The boy grew up to found the great Chandela dynasty. When he was established as a ruler, he had a dream-visitation from his mother, who implored him to build temples that would reveal human passions, and in doing so bring about a realization of the emptiness of human desire. Chandravarman began the construction of the first of the temples, successive rulers added to the fast growing complex.

Picture provided by Laurence RogersonYet another theory is that the erotica of Khajuraho, and indeed of other temples, had a specific purpose. In those days when boys lived in hermitages, following the Hindu law of being “brahmacharis” until they attained manhood, the only way they could prepare themselves for the worldly role of ‘householder’ was through the study of these sculptures and the earthly passions they depicted.

If the temples of Khajuraho can be said to have a theme, it is woman. A celebration of woman and her myriad moods and facets- Writing letters, applying kohl to her eyes, brushing her hair, dancing with joyous abandon playing with her child. Woman – innocent, coquettish, smiling – infinitely seductive, infinitely beautiful. Depicted in a wealth of detail, sharply etched, sculpted with consummate artistry. The philosophy of the age dictated the enjoyment of the delights of arth (material wealth) and kama (sensual pleasures) while performing one’s dharma (duty) as the accepted way of life for the grihastha (householder). Hence, the powerful combination of the visual and sensual pleasures combined with the duty attributed to the worship of the Dieties brings about a powerful transformation of the body and the soul. To include all of these aspects of life in one’s early years makes it easier to renounce them without regret or attachment as one moves on to one’s next stages of life toward moksha (liberation).

The Khajuraho temples do not contain sexual or erotic art inside the temple or near the deities; however, some external carvings bear erotic art. Also, some of the temples that have two layers of walls have small erotic carvings on the outside of the inner wall. There are many interpretations of the erotic carvings. They portray that, for seeing the deity, one must leave his or her sexual desires outside the temple. They also show that divinity, such as the deities of the temples, is pure like the atman, which is not affected by sexual desires and other characteristics of the physical body. It has been suggested that these suggest tantric sexual practices. Meanwhile, the external curvature and carvings of the temples depict humans, human bodies, and the changes that occur in human bodies, as well as facts of life. Some 10% of the carvings contain sexual themes; those reportedly do not show deities, they show sexual activities between people. The rest depict the everyday life of the common Indian of the time when the carvings were made, and of various activities of other beings. For example, those depictions show women putting on makeup, musicians, potters, farmers, and other folks. Those mundane scenes are all at some distance from the temple deities. A common misconception is that, since the old structures with carvings in Khajuraho are temples, the carvings depict sex between deities.

While the sexual nature of these carvings have caused the site to be referred to as the Kamasutra temple, they do not illustrate the meticulously described positions. Neither do they express the philosophy of Vatsyayana’s famous sutra. As “a strange union of Tantrism and fertility motifs, with a heavy dose of magic” they belie a document which focuses on pleasure rather than procreation. That is, fertility is moot.

Dr. Devangana Desai points out that there is a misunderstanding regarding representation of homosexuality in Khajuraho sculptures. It is not depicted in Khajuraho sculptures. There are two sculptures mistaken as gay figures:

1. The much talked about scene, often misunderstood as depicting lesbian love, is the head-down sculpture on the north wall of the Vishvanatha temple of the site. The top figure whose back is seen in the panel looks like a woman, but is actually a man, whose genitals can be seen from below. The figure is mistaken for a woman because of the hair tied in a bun at the back, which was a male hair style prevalent in medieval India.

2. The other, often misunderstood sculpture is on the south wall of the Devi Jagadamba temple. Here a bearded Shaiva (Kapalika) ascetic threatens a nude Kshapanaka monk to join his religious order, by holding his organ and raising his other hand to hit him. The monk is shown with folded hands as if surrendering. These figures represent two characters of the allegorical play Prabodhachandrodaya, staged in the Khajuraho region in the 11th century. There is no gay relationship involved in the sculptural scene.

History

In the twenty-seventh century of Kali yuga, the Mlechcha invaders started attacking North India. Some Bargujar Rajputs moved eastward to central India; they ruled over the Northeastern region of Rajasthan, called Dhundhar, and were referred to as Dhundhel/Dhundhela in ancient times, for the region they governed. Later on they called themselves Bundelas and Chandelas; those who were in the ruling class having gotra Kashyap were definitely all Bargujars; they were vassals of Gurjara – Pratihara empire of North India, which lasted from 500 C.E. to 1300 C.E. and at its peak the major monuments were built. The Bargujars also built the Kalinjar fort and Neelkanth Mahadev temple, similar to one at Sariska National Park, and Baroli, being Shiva worshippers. The city was the cultural capital of Chandela Rajputs, a Hindu dynasty that ruled this part of India from the 10-12th centuries. The political capital of Chandelas was Kalinjar. The Khajuraho temples were built over a span of 200 years, from 950 to 1150. The Chandela capital was moved to Mahoba after this time, but Khajuraho continued to flourish for some time. Khajuraho has no forts because the Chandel Kings never lived in their cultural capital.

The whole area was enclosed by a wall with eight gates, each flanked by two golden palm trees. There were originally over 80 Hindu temples, of which only 25 now stand in a reasonable state of preservation, scattered over an area of about 20 square kilometres (8 sq mi). Today, the temples serve as fine examples of Indian architectural styles that have gained popularity due to their explicit depiction of sexual life during medieval times. Locals living in the Khajuraho village always knew about and kept up the temples as best as they could. They were pointed out to an Englishman in late 19th century but the jungles had taken a toll on all the monuments.

Architecture

The temples are grouped into three geographical divisions: western, eastern and southern. The Khajuraho temples are made of sandstone, they didn’t use mortar the stones were put together with mortise and tenon joints and they were held in place by gravity. This form of construction requires very precise joints. The columns and architraves were built with megaliths that weighed up to 20 tons. Lakshmana temple at Khajuraho, a panchayatana temple. Two of the four secondary shrines can be seen. Another view.

These temples of Khajuraho have sculptures that look very realistic and are studied even today.

The Saraswati temple on the campus of Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, India is modeled after the Khajuraho temple. The scale at which the work was undertaken is enormous. It covers twice the area of the Parthenon in Athens and is 1.5 times high, and it entailed removing 200,000 tonnes of rock. It is believed to have taken 7,000 labourers 150 years to complete the project. The rear wall of its excavated courtyard 276 feet (84 m) 154 feet (47 m) is 100 ft (33 m) high. The temple proper is 164 feet (50 m) deep, 109 feet (33 m) wide, and 98 feet (30 m) high.

Statues and carvings

Discuss article