Conspiracy : Shergar and a 25-year-old mystery

Source : http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/racing/shergar-and-a-25yearold-mystery-778025.html

Was it the IRA? Or the Mafia? Or even Colonel Gadaffi? The abduction of the Derby-winning racehorse remains one of the great unsolved crimes of the twentieth century

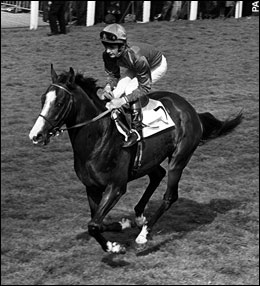

The kidnapping of champion racehorse Shergar remains one of Britains most baffling whodunnits. For two decades, the disappearance of the celebrated Derby winner has been shrouded in a fog of mystery and conspiracy theories. Shergar (born 1978. Sire: Great Nephew, Dam: Sharmeen) was an acclaimed racehorse, and winner of the 1981 Epsom Derby by a record 10 lengths, the longest winning margin in the race’s 226-year history. This victory earned him a spot in The Observer newspaper’s 100 Most Memorable Sporting Moments of the Twentieth Century. A bay colt with a distinctive white blaze, Shergar was named European Horse of the Year in 1981. Bred by his owner Prince Karim Aga Khan IV in County Kildare, close to the stud from which he was kidnapped, Shergar began training with Michael Stoute at Newmarket. His debut race in 1981 was the Guardian Classic Trial at Sandown Park. Racing correspondent Richard Baerlein, after watching the colt win by 10 lengths famously advised race-goers that “at 8-1, Shergar for the Derby, now is the time to bet like men”.

On Tuesday 8 February 1983, a foggy winter’s evening in Ireland, a group of men wearing balaclavas and armed with guns turned up at the Ballymany Stud Farm in Co Kildare. It was a visit that would go down in horseracing history. With one hostage already taken Jim Fitzgerald, the stud’s head groom the men had come to take another. “We’ve come for Shergar,” they said. “We want £2m for him.”

Shergar was arguably the greatest racehorse to have ever lived. But 25 years after he was kidnapped from Ballymany the mystery of exactly what happened to him after he was snatched that night still lingers.

Then, as now, the story was one that gripped the world. From racing enthusiasts to ordinary members of the public, everyone wanted to know who had taken Shergar, why they had done so and what became of him. And then, as now, no definite answers were forthcoming.

The theories are numerous with the IRA, Colonel Gadaffi and the Mafia featuring among the most lurid. One story suggests that the IRA kidnapped the horse for Gadaffi in return for weapons. Gadaffi’s motive for wanting the horse was said to stem from his belief that he should lead the Islamic people rather than the direct descendants of the Prophet Mohamed, such as the Aga Khan one of Shergar’s owners.

Another theory is that the New Orleans mafia took Shergar. Frenchman Jean Michel Gambet, so the tale went, borrowed money from the mafia to buy a horse from the Aga Khan, the deal collapsed and Gambet apparently spent the money. Gambet was found dead in a car in Kentucky, but the mafia felt they were still owed a horse from the Aga Khan and took Shergar.

However, the most probable and likely version of events is that Shergar was taken by the Provisional IRA, who demanded a multimillion-pound ransom from the owners to fund purchases of weapons so it could continue its fight against the British presence in Northern Ireland.

On the race track, Shergar’s racing career was short but incredibly successful. The bay colt, with the distinctive white blaze on his nose, raced just eight times in a year, winning six times and banking nearly £500,000 in prize money before he was retired to stud in October 1981.

Undoubtedly his most famous victory came in the Epsom Derby in 1981. Ridden by the 19-year-old jockey Walter Swinburn, Shergar started as favourite and obliterated the field, winning by 10 lengths the biggest victory margin in the race’s 226-year history. It secured the horse’s place in sporting immortality and in the hearts of the nation.

Away from the race track there was relief when it was announced that Shergar would be put to stud in Ireland and not, as many in the horse-racing world had feared, in America. As a result of his on-the-track glories, a syndicate headed by the Aga Khan was able to charge up to £80,000 a time for Shergar’s services. He covered 35 mares in his first season with a further 55 planned for 1983.

However, everything changed on that Tuesday in 1983. Shortly after 8.30pm, Jim Fitzgerald heard a knock at his door. When his son, Bernard, answered it he was confronted by the three men.

At gunpoint Mr Fitzgerald, then 53, was forced to take the three men and the rest of their gang to Shergar’s stable and help them load the horse into a horsebox they had brought with them. After that he was driven away from the stud and thrown out of the car with instructions for representatives of the Aga Khan as to how they could negotiate with the kidnappers. After his release, Mr Fitzgerald phoned the stud manager, Ghislain Drion. Mr Drion phoned Shergar’s vet, Stan Cosgrove, who had also bought a share in the horse. Mr Cosgrove, in turn, called his friend, the former Army officer Captain Sean Berry who rang Alan Dukes, the local MP who was also the Irish finance minister.

Amazingly it was more than four hours before the Irish police were alerted and the police investigation into one of sport’s greatest whodunnits began. But, from both the kidnappers’ and the Garda’s point of view, the Shergar episode was fraught with serious problems from the outset.

The first problem for the police was the kidnapping’s timing. Shergar was taken the day before Ireland’s biggest racehorse sale a day on which horseboxes were driven on roads across the country, making an impossible task to find the box containing Shergar.

The investigation was further complicated because officers from both Dublin and Co Kildare were put on the case. The two forces reportedly refused to share information and believed that they were in direct competition with each other.

There was also a feeling that the police investigation was unlikely to be successful under the command of Chief Supt James “Spud” Murphy and his determination to use mediums and psychics to solve the case. He once famously told journalists: “A clue? That is something we haven’t got.”

However, one common factor in most of the conspiracy theories was the probable involvement of the Provisional IRA. This view was given greater weight in the 1990s when the IRA member-turned-informer Sean O’Callaghan alleged that the paramilitary group was behind the kidnapping.

The IRA, in desperate need of money to buy weapons, had previously kidnapped rich businessmen to raise ransom money. However, the sight of the kidnap victims’ families and loved ones crying on television was thought to be costing them support in their Republican heartlands.

This, according to O’Callaghan, gave rise to the plot to kidnap Shergar. But, in the first of a series of blunders, the IRA underestimated the outrage that such an act would spark in a country with such a strong love of horses.

They also failed to realise that the horse was owned by a syndicate and not just the Aga Khan. In fact, the Shia Muslim prince owned only six of the 40 shares and it would have required the agreement of all 35 members of the syndicate for the £2m ransom to be paid. Doing so would have left the syndicate open to subsequent extortion threats and it was never likely they would all agree. Even after the ransom demand was lowered to £40,000 a figure of £1,000 per share the syndicate members still refused to pay it. O’Callaghan explained that what was originally thought to be a foolproof plan quite quickly turned into a disaster. “A cell thought: ‘Why not kidnap Shergar?’ The horse had no family. They were convinced that the Aga Khan would pay up. It couldn’t go wrong. This was going to be a quick way to make money, very quick. But, if they had thought about it, they would have realised that paying a ransom would have left the Aga Khan and the others open to all kinds of extortion threats. The money was a non-starter.”

What happened next is the subject of debate. O’Callaghan says that he was told that the horse was shot within hours of it being kidnapped after it became aggressive and hurt its leg. The gang, which had no experience of handling a highly strung animal and believing that they would not get any money for a lame horse, shot it dead.

O’Callaghan added: “One of the gang suggested to me that Shergar was killed within hours [of being taken]. Shot dead. He went demented in the horsebox and badly injured his leg. They had to kill him because they couldn’t call a vet they had the most recognisable horse in the world on their hands. [It was a] total cock-up from start to finish.”

However those close to the horse, including his former jockey Walter Swinburn, say that this theory does not ring true because Shergar was a very calm horse and would not have been aggressive. The other story is that the gang, having realised that their ransom demand was a non-starter, had decided to return Shergar and abandon the bungled plot.

But, with the police operation now in full swing and Garda searching for the Shergar throughout Ireland, the gang decided that they had no option but to kill the horse and bury his remains.

An IRA source, who was a close friend of one of the kidnappers, described how the horse allegedly met his end. “Shergar was machine-gunned to death,” he said. “There was blood everywhere and the horse even slipped on his own blood. There was lots of cussin’ and swearin’ because the horse wouldn’t die. It was a very bloody death. It was several minutes before the horse, which was in agony, bled to death.”

On hearing how the world’s most famous racehorse had met with such a grisly and undignified end, Mr Fitzgerald simply declared: “That’s not a very nice thing to do. Shergar was a grand horse and he deserved better.”

The most often repeated stories surrounding Shergar’s death, while never proven, seem to have been gradually accepted in Ireland as the truth. But even today, 25 years after his disappearance, little is known of Shergar’s final resting place.

He is rumoured to be buried 100 miles from the Ballymany Stud in a mountainside grave in Ballinamore, Co Leitrim, but the failure to find his body means that one thing is certain: after a murder-mystery that has lasted more than quarter of a century and cost Ireland one of sport’s greatest animals, there were no winners in this sad tale.

The IRA never got the ransom money it demanded, horse-racing was robbed of potentially one of its greatest studs and the horse’s owners did not receive a penny from Shergar’s life insurance policy because a body was never found.

And, while the theories and debate about Shergar’s disappearance will probably rage for another 25 years, Walter Swinburn says he is resigned to the fact that he will never truly know what happened to the horse he described as the greatest he has ever ridden: “It’s been 25 years now and I must have heard a million and one theories about what happened to him. But I don’t think anyone will ever find out what really happened to Shergar. I just pray he didn’t suffer too much. But you can’t even be sure of that.”