Roman deadly ‘Gate to Hell’ Mystery solved

A cave ancient Romans believed to be a gate to the underworld was so deadly that it killed all animals who entered its proximity, while not harming the human priests who led them. Now scientists believe they have figured out why – a concentrated cloud of carbon dioxide that suffocated those who breathed it.

It sounds like the plot for a new Indiana Jones film.

Archaeologists say they have discovered the ‘Gates of Hell’, the mythical portal to the underworld in Greek and Roman legend.

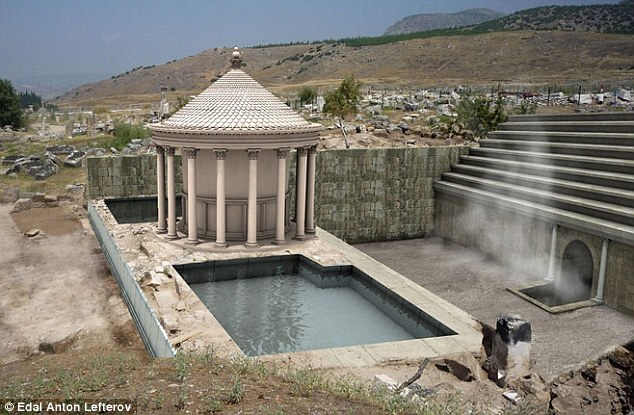

The site, in the ancient Phrygian city of Hierapolis, now Pamukkale in southwestern Turkey, is said to closely match historical descriptions of what was known as Ploutonion in Greek and Plutonium in Latin. If there’s a highway to hell, there’s probably a gate to hell—well, there is. It’s located in what was the ancient Greco-Roman city of Hierapolis, which is now in modern-day Turkey.

Called Plutonium after Pluto, the gate was thought to be an opening to the underworld. It was first described by the ancient Greek geographer Strabo and Roman author Plinius. When Strabo visited, he described a thick vapor that would overtake the gate. During religious ceremonies, the castrated priests who entered Plutonium would come out alive. But “bulls that are led into it fall and are dragged out dead; and I threw in sparrows and they immediately breathed their last and fell.”

For a while, we only had stories, but the gateway to hell was rediscovered a few years ago with dead birds near the opening. But what causes such strange happenings? Thankfully, another group of researchers set to find out, as described in a study released this week in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Describing the site, the Greek geographer Strabo (64/63 BC — about 24 A.D.) said: ‘This space is full of a vapor so misty and dense that one can scarcely see the ground. ‘Any animal that passes inside meets instant death. I threw in sparrows and they immediately breathed their last and fell.’

Drop Dead

After analyzing the gases below and around the gate, scientists found deadly concentrations of carbon dioxide — up to 91 percent. The CO2 being emitted from the mouth of the gate ranged from 4 to 53 percent, with lower amounts the higher you get from the ground.

Carbon dioxide was emitted at such dangerous levels that the gas would kill you within a minute. So how the heck did the priests survive? Strabo thought, perhaps, the priests who dared to enter the Plutonium didn’t drop dead because they were castrated. He also noted that the priests bent down, held their breath, and only went in so far.

The lead author of the study, volcanologist Hardy Pfanz, thinks the priests just understood what was going on — they knew certain times of day were better to go down and were tall enough that the gases didn’t reach them. They were also taller than the poor animals that entered the cave, and that probably helped them stay above the smothering vapor.

“They … knew that the deadly breath of [the mythical hellhound] Kerberos only reached a certain maximum height,” Pfanz told Science Magazine.

Scientists say those vapors are still released in amounts that can kill insects, birds and mammals. The gate is located in the Babadag fracture zone, an active seismic zone that originally created openings that allowed the carbon dioxide to escape the Earth.

The ancient city was founded around 190BC by Eumenes II, King of Pergamum. It was taken over by the Romans in 133 B.C..

Under Roman rule the city flourished. There were temples, a theater and people flocked to bathe in the hot springs which were believed to have healing properties.

Today Pamukkale is well known for the stunning white travertine terraces which are the result of the hot springs.

Mr D’Andria has conducted extensive archaeological research at Hierapolis and two years ago he claimed to discover there the tomb of Saint Philip, one of the 12 apostles of Jesus Christ.

D’Andria also found the remains of a pool and the steps placed above the cave which match the descriptions of the site in ancient sources.