Why many Egyptian statues have broken noses?

You’ve probably noticed that a lot of ancient Egyptian statues have broken noses. Now, for the first time, an exhibition is explaining why. And it’s probably not for the reason you think.

“The most common question we get at the Brooklyn Museum about the Egyptian collection of art is ‘Why are the noses broken?’” Bleiberg told artnet News. “It seemed like it would be a good idea to actually figure out what the answer is.”

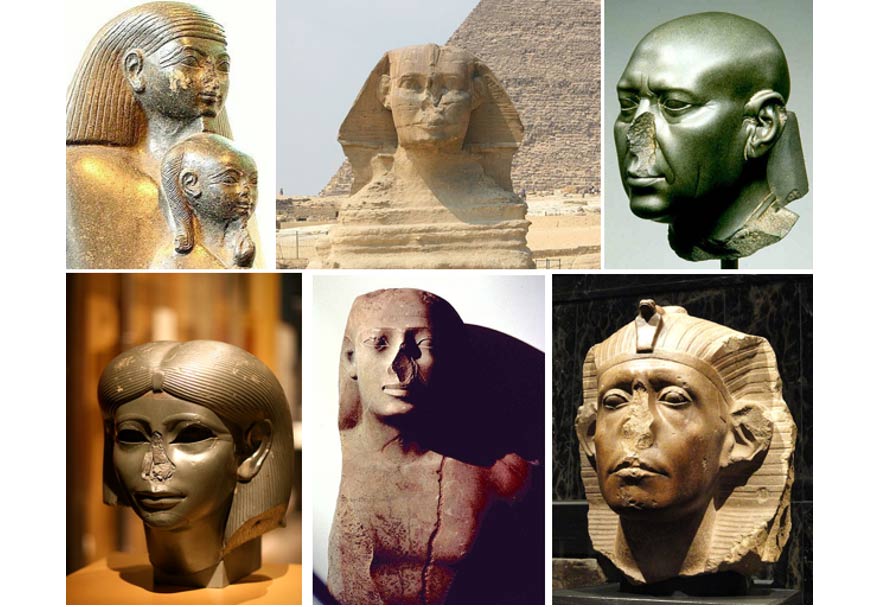

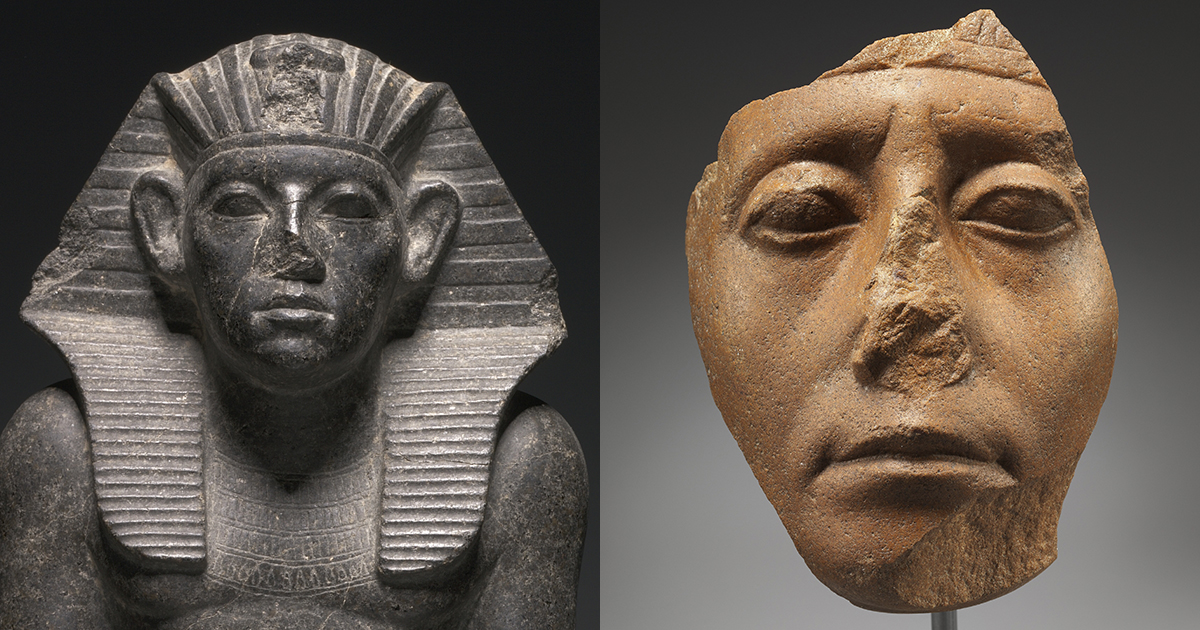

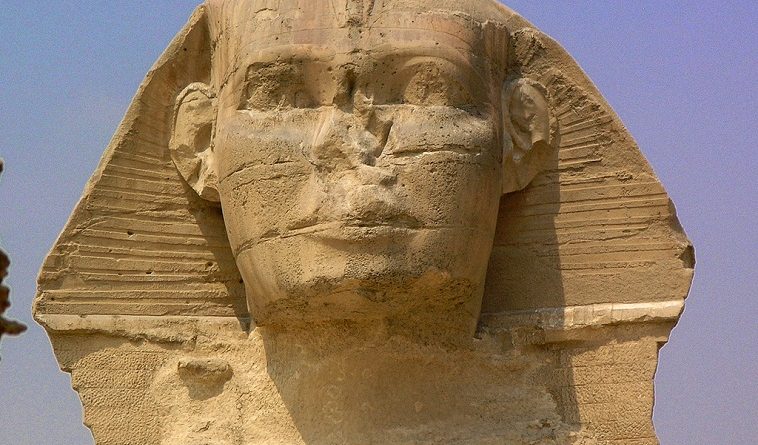

With sculptures this old, it seems natural that there would be some wear and tear, or that noses might shatter when pieces inevitably fall over at some point over the millennia. But 2-D relief works often show the same type of damage to the face, suggesting a deliberate pattern.

As it turns out, Christians and even some pharaohs actually had a habit of vandalizing artwork due to an entrenched culture of iconoclasm. The deliberate destruction of artworks was a way of counteracting the cultural and political power of the image—a world view that resonates across the centuries, as seen in the destruction wrought by ISIS in recent years at ancient historical sites in the Middle East.

“The Egyptians made these images as a resting place for a supernatural being. These are the places where human beings can have direct contact with the gods, or deceased human beings who have been transformed into a divine spirit,” explained Bleiberg. “When they are damaged, it interferes with the communication between the supernatural and people here on earth.”

While one might think that communication with spirits would be desirable, sometimes those who were seeking to concentrate their power wanted the exact opposite—to break it off.

And when you think about how hard these basalt and granite sculptures are, it becomes even more obvious that this defacement was intentional. “These would have been quite difficult to damage,” added Weissberg. “The sheer difficulty and effort involved in making modifications to these works really underscores the urgency and perceived importance of these objects.”

“Egyptian state religion,” Bleiberg explained, was seen as “an arrangement where kings on Earth provide for the deity, and in return, the deity takes care of Egypt.” Statues and reliefs were “a meeting point between the supernatural and this world,” he said, only inhabited, or “revivified,” when the ritual is performed. And acts of iconoclasm could disrupt that power.

“The damaged part of the body is no longer able to do its job,” Bleiberg explained. Without a nose, the statue-spirit ceases to breathe, so that the vandal is effectively “killing” it. To hammer the ears off a statue of a god would make it unable to hear a prayer. In statues intended to show human beings making offerings to gods, the left arm — most commonly used to make offerings — is cut off so the statue’s function can’t be performed (the right hand is often found axed in statues receiving offerings).

“In the Pharaonic period, there was a clear understanding of what sculpture was supposed to do,” Bleiberg said. Even if a petty tomb robber was mostly interested in stealing the precious objects, he was also concerned that the deceased person might take revenge if his rendered likeness wasn’t mutilated.

The prevalent practice of damaging images of the human form — and the anxiety surrounding the desecration — dates to the beginnings of Egyptian history. Intentionally damaged mummies from the prehistoric period, for example, speak to a “very basic cultural belief that damaging the image damages the person represented,” Bleiberg said. Likewise, how-to hieroglyphics provided instructions for warriors about to enter battle: Make a wax effigy of the enemy, then destroy it. Series of texts describe the anxiety of your own image becoming damaged, and pharaohs regularly issued decrees with terrible punishments for anyone who would dare threaten their likeness.

Indeed, “iconoclasm on a grand scale…was primarily political in motive,” Bleiberg writes in the exhibition catalog for “Striking Power.” Defacing statues aided ambitious rulers (and would-be rulers) with rewriting history to their advantage. Over the centuries, this erasure often occurred along gendered lines: The legacies of two powerful Egyptian queens whose authority and mystique fuel the cultural imagination — Hatshepsut and Nefertiti — were largely erased from visual culture.

“Hatshepsut’s reign presented a problem for the legitimacy of Thutmose III’s successor, and Thutmose solved this problem by virtually eliminating all imagistic and inscribed memory of Hatshepsut,” Bleiberg writes. Nefertiti’s husband Akhenaten brought a rare stylistic shift to Egyptian art in the Amarna period (ca. 1353-36 BC) during his religious revolution. The successive rebellions wrought by his son Tutankhamun and his ilk included restoring the longtime worship of the god Amun; “the destruction of Akhenaten’s monuments was therefore thorough and effective,” Bleiberg writes. Yet Nefertiti and her daughters also suffered; these acts of iconoclasm have obscured many details of her reign.

Ancient Egyptians took measures to safeguard their sculptures. Statues were placed in niches in tombs or temples to protect them on three sides. They would be secured behind a wall, their eyes lined up with two holes, before which a priest would make his offering. “They did what they could,” Bleiberg said. “It really didn’t work that well.”

Speaking to the futility of such measures, Bleiberg appraised the skill evidenced by the iconoclasts. “They were not vandals,” he clarified. “They were not recklessly and randomly striking out works of art.” In fact, the targeted precision of their chisels suggests that they were skilled laborers, trained and hired for this exact purpose. “Often in the Pharaonic period,” Bleiberg said, “it’s really only the name of the person who is targeted, in the inscription. This means that the person doing the damage could read!”

The understanding of these statues changed over time as cultural mores shifted. In the early Christian period in Egypt, between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, the indigenous gods inhabiting the sculptures were feared as pagan demons; to dismantle paganism, its ritual tools — especially statues making offerings — were attacked. After the Muslim invasion in the 7th century, scholars surmise, Egyptians had lost any fear of these ancient ritual objects. During this time, stone statues were regularly trimmed into rectangles and used as building blocks in construction projects.

“Ancient temples were somewhat seen as quarries,” Bleiberg said, noting that “when you walk around medieval Cairo, you can see a much more ancient Egyptian object built into a wall.”

Such a practice seems especially outrageous to modern viewers, considering our appreciation of Egyptian artifacts as masterful works of fine art, but Bleiberg is quick to point out that “ancient Egyptians didn’t have a word for ‘art.’ They would have referred to these objects as ‘equipment.'” When we talk about these artifacts as works of art, he said, we de-contextualize them. Still, these ideas about the power of images are not peculiar to the ancient world, he observed, referring to our own age of questioning cultural patrimony and public monuments.

nonsense. Christians were not trying to keep demons away by vandalizing noses.

noses being knocked off is purely racial. certain people trying to erase people they don’t like. mainly trying to make it look as though those Egyptians were not with narrow noses and straight hair.