Monsters on the Rio Grande

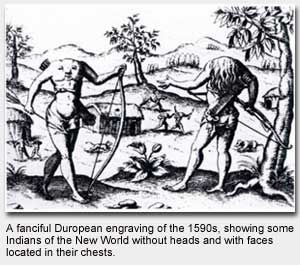

Most peoples of the world have myths and legends of monsters and other fanciful creatures that spring from humanity’s fertile imagination. For a thousand years before Columbus, Europeans busily assembled a reservoir of lore about one eyed beasts, dragons, giants, amazons and headless monsters that breathed through their stomachs.

The Spaniards who settled New Mexico at the beginning of the colonial era brought with them their Old World notions of monsters and mythical beings.

For example, when Juan de Oñate led an expedition from the upper Rio Grande westward to Arizona in 1604, he was accompanied by Father Francisco de Escobar. The priest was an expert in Indian languages.

In speaking to natives along the Colorado River, he claimed they told him of curious beings who lived beyond the horizon, monstrous and never seen in our time.

Among them were humanlike creatures with large ears that dragged on the ground; others born with but a single leg and foot; a tribe of people that slept standing up; and another tribe that slept under water. These clearly were not Indian notions, but the friar’s projection of European myths.

There exists a rare book written in French and published in Paris in 1784 containing engravings of monsters that are supposed to inhabit New Mexico. In its pages are several images of harpies, which are birds or animals with human heads and horns.

Author of this bizarre volume was a prince of the French royal household who later ascended to the throne as Louis XVIII. In the book credits, he gave himself the imaginative titles of Count of Barcelona and Viceroy of New Mexico.

In the folk culture along the Rio Grande, one finds persistent tales of a fabled monster known as the basilisk, or in Spanish, el basilisco. The legend originated in North Africa, was carried to Spain by the Moors and later transferred to the colonies in America.

The basilisk is variously described as a large lizard, serpent or dragon. In all cases, its breath or its look, when falling upon a human, is said to be fatal.

In Spanish myth, the creature is born from an egg laid by a rooster. But in our own Southwest, it is said to spring directly from the hen without benefit of an egg. As to the deadly effect of the monster’s eye, the Rio Grande version of the story follows belief in other parts of the Hispanic world.

If the basilisk sees someone first, that person dies. But if the situation is reversed and the creature is caught unaware and observed by a human first, then it dies.

A basilisk once found a home in a magpie’s nest in a tree that grew beside the Albuquerqueto-El Paso wagon road. Many an unsuspecting traveler was killed by its deadly gaze. Finally, a mirror was placed near the nest. The beast looked at its own reflection and perished.

The same story, with slight variations, occurs in such widely separated places as Spain, Guatemala and Chile.

Another common tale in New Mexico concerned a monster snake. This was a legend that arose from American Indians.

The oldest version comes from Pecos Pueblo. Lt. James Abert wrote in 1846 about a giant snake god that had once been kept in an underground kiva and fed infants for nourishment.

His large appetite contributed to the extinction of the pueblo by the late 1830s.

Of this beast, Santa Fe trader Josiah Gregg reported: Once I met a New Mexican rancher who asserted that upon entering Pecos Pueblo one winter’s morning, he saw the huge trail of the reptile in the snow, as large as that of an ox being dragged.

The Indians of Taos Pueblo are also reputed to have possessed in the 19th century a giant rattlesnake that dined on their babies during important feast days. At the time of the 1847 uprising, American military forces attacked the pueblo.

In the midst of the battles, the snake god was seen to be in danger. So a brave Indian placed it under blankets in a handcart and rushed it to safety through a hail of bullets. But in the process, the rescuer was shot to pieces.

Historian Marc Simmons is author of numerous books on New Mexico and the Southwest. His column appears Saturdays. by Marc Simmons