Secrets of the Voodoo Tomb – Unexplained Mysteries

Among the sites associated with New Orleans voodoo is the tomb of its greatest figure, Marie Laveau. For several decades this “voodoo queen” held New Orleans spellbound-figuratively, of course, but some would say literally, as legends of her occult powers continue to captivate. She staged ceremonies in which participants became possessed by loas (voodoo spirits) and danced naked around bonfires; she dispensed charms and potions called gris-gris, even saving several condemned men from the gallows; and she told fortunes, healed the sick, and herself remained perpetually youthful while living for more than a century-or so it is said (Hauck 1996; Tallant 1946).

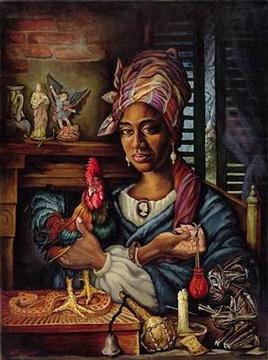

Marie Laveau

A “free person of color,” Marie Laveau was the illegitimate daughter of a rich Creole plantation owner, Charles Laveaux, and his mistress Marguerite (who was reportedly half black, half Indian). Marie was probably born about 1794. At the age of twenty-five she married a carpenter named Jacques Paris, also a free person of color, who soon went missing and was presumed dead. Following the custom of the time, she began calling herself the “Widow Paris.” Soon, she entered a common-law marriage with one Christophe de Glapion with whom she would have fifteen children, but as late as 1850 a newspaper still referred to her as “Marie Laveaux, otherwise Widow Paris” (Tallant 1946, 67).

The Widow Paris learned her craft from a “voodoo doctor” known variously as Doctor John, John Bayou, and other appellations, and by 1830 she was one of several New Orleans voodoo queens. She soon came to dominance, taking charge of the rituals held at Congo Square and selling gris-gris throughout the social strata. Marie worked as a hairdresser, which took her into the homes of the affluent, and she reportedly developed a network of informants. According to Tallant (1946, 64), “No event in any household in New Orleans was a secret from Marie Laveau.” She parlayed her knowledge into a position of considerable influence, as she told fortunes, gave advice on love, and prepared custom gris-gris for anyone needing to effect a cure, charm, or hex.

If she did not actually save anyone from a sentence of death, she allowed such stories to flourish. “The Widow Paris thrived on publicity,” observes Tallant (1946, 58). “Legend after legend spread about her and she seems to have enjoyed them all.”

The legend of her perpetual youth is easily explained: She had a look-alike daughter, Marie Laveau II, who followed in her footsteps. About 1875 the original Marie, bereft of her youth and memory, became confined to her home on Rue St. Ann and did not leave until claimed by death some six years later. “It was then,” reports Tallant (1946, 73), “that the strangest part of the entire Laveau mystery became most noticeable. For Marie Laveau still walked the streets of New Orleans, a new Marie Laveau, who also lived in the St. Ann Street Cottage.”

|

The Wishing Tomb

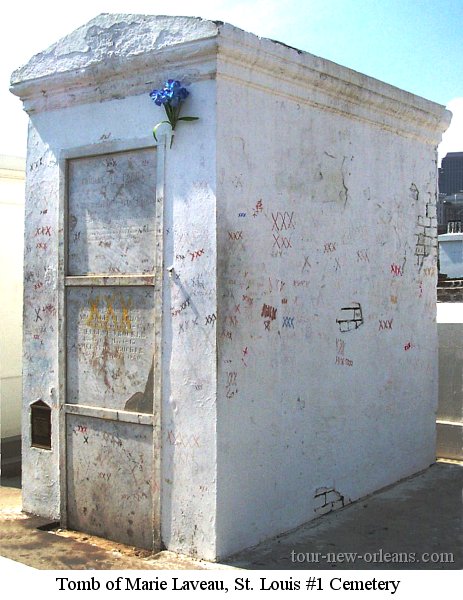

Controversy persists over where Marie Laveau and her namesake daughter are buried. Some say the latter reposes in the cemetery called St. Louis No. 2 (Hauck 1996) in a “Marie Laveau Tomb” there. However, that crypt most likely contains the remains of another voodoo queen named Marie, Marie Comtesse. Numerous sites in as many cemeteries are said to be the final resting place of one or the other Marie Laveau (Tallant 1946, 129), but the prima facie evidence favors the Laveau-Glapion tomb in St. Louis No. 1 (figure 1). It comprises three stacked crypts with a “receiving vault” below (that is, a repository of the remains of those displaced by a new burial). |

That tomb’s carved inscription records the name, date of death, and age (62) of Marie II: “Marie Philome Glapion, décédé le 11 Juin 1897, ágée de Soixante-deux ans.” A bronze tablet affixed to the tomb announces, under the heading “Marie Laveau,” that “This Greek Revival Tomb Is Reputed Burial Place of This Notorious ‘Voodoo Queen’ . . . ,” presumably a reference to the original Marie (see figure 2). Corroborative evidence that she was interred here is found in her obituary (“Death” 1881) which notes that “Marie Laveau was buried in her family tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.” Guiley (2000) asserts that, while Marie Laveau I is reportedly buried here, “The vault does not bear her name.” However, I was struck by the fact that the initial two lines of the inscription on the Laveau-Glapion tomb read, “Famille Vve. Paris / née Laveau.” Obviously, “Vve.” is an abbreviation for Veuve, “Widow”; therefore the phrase translates, “Family of the Widow Paris, born Laveau”-namely Marie Laveau I. I take this as evidence that here is indeed the “family tomb.” Robert Tallant (1946, 127) suggests: “Probably there was once an inscription marking the vault in which the first Marie was buried, but it has been changed for one marking a later burial. The bones of the Widow Paris must lie in the receiving vault below.”

The Laveau-Glapion tomb is a focal point for commercial voodoo tours. Some visitors leave small gifts at the site-coins, Mardi Gras beads, candles, etc.-in the tradition of voodoo offerings. Many follow a custom of making a wish at the tomb. The necessary ritual for this has been variously described. The earliest version I have found (Tallant 1946, 127) says that people would “knock three times on the slab and ask a favor,” noting: “There are always penciled crosses on the slab. The sexton washes the crosses away, but they always reappear.” A more recent source advises combining the ritual with an offering placed in the attached cup: “Draw the X, place your hand over it, rub your foot three times against the bottom, throw some silver coins into the cup, and make your wish” (Haskins 1990). Yet again we are told that petitioners are to “leave offerings of food, money and flowers, then ask for Marie’s help after turning around three times and marking a cross with red brick on the stone” (Guiley 2000, 216).

When I visited the tomb it was littered with markings, including single Xs; an occasional cross, heart, pentagram, etc.; and a few inscriptions or other graffiti, sometimes accompanied by initials (figure 3). One comment read: “Her eyes / lit up with Fire / For the dreams / she entertained . . . / Seems something in her / knew already / just how well / They’d burn. / A.R.P. / 11-19-00.” The predominant markings were sets of three Xs-suggesting that the folk practice is undergoing transition (the specified number of raps, turns, etc. apparently becoming transferred to the number of Xs).

Although some of the markings are done in black (as from charcoal), most are rendered in a rusty red from bits of crumbling brick. One New Orleans guidebook says of the wishing tomb: “The family who own it have asked that this bogus, destructive tradition should stop, not least because people are taking chunks of brick from other tombs to make the crosses. Voodoo practitioners-responsible for the candles, plastic flowers, beads, and rum bottles surrounding the plot-deplore the practice, too, regarding it as a desecration that chases Laveau’s spirit away” (Cook 1999). Echoing that view, another guidebook advises: “On the St. Louis tour, please don’t scratch Xs on the graves; no matter what you’ve heard, it is not a real voodoo practice and is destroying fragile tombs” (Herczog 2000).

The scuttlebutt, according to the professional guide I commissioned (Krohn 2000), is that the practice may have evolved from ordinary graffiti which was then transformed by an early cemetery guide into a pseudo-voodoo custom that brought him tips. One writer wryly observes of the wishing practice that there is “no word on success rates” (Dickinson 1997).

Perturbed Spirit

Given the belief that Marie Laveau’s spirit can be invoked to grant wishes, it was inevitable that there would be alleged sightings. According to the author of Haunted City (Dickinson 1997, 131): “Tour guides tell of a Depression-era vagrant who fell asleep atop a tomb in the cemetery and was awakened to the sound of drums and chanting. Stumbling upon the tomb of Marie Laveau, he encountered the ghosts of dancing, naked men and women, led by a tall woman wrapped in the coils of a huge snake.” Or so tour guides tell. But did the “vagrant” perhaps pass out from drink and have a vivid dream or hallucination? How much has the story been embellished in the intervening two-thirds century or so? Do we know that the alleged event even occurred? These are among the problems with such anecdotal evidence.

The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits asserts: “One popular legend holds that Marie I never died, but changed herself into a huge black crow which still flies over the cemetery.” Indeed, “Both Maries are said to haunt New Orleans in various human and animal forms” (Guiley 2000). Note the anonymity inherent in such phrases as “popular legend” and the passive-voice construction “are said to.” In addition to her tomb, Marie also allegedly haunts other sites. For example, according to Hauck (1996), “Laveau has also been seen walking down St. Ann Street wearing a long white dress.” Providing a touch of what literary critics call verisimilitude (an appearance of truth), Hauck adds, “The phantom is that of the original Marie, because it wears her unique tignon, a seven-knotted handkerchief, around her neck.” But Hauck has erred: Marie in fact “wore a large white headwrap called a tignon tied around her head,” says her biographer Gandolfo (1992, 19), which had “seven points folded into it to represent a crown.” Gandolfo, who is also an artist, has painted a striking portrait of Marie Laveau wearing her tignon, which is displayed in the gift shop of his New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum (and reproduced in Gandolfo 1992, 1).

With a bit of literary detective work we can track the legend-making process in one instance of Laveau ghostlore. In his Haunted Places: The National Directory, Hauck (1996) writes of Marie: “Her ghost and those of her followers are said to practice wild voodoo rituals in her old house. . . .” But are said to by whom? His list of sources for the entry on Marie Laveau includes Susy Smith’s Prominent American Ghosts (1967), his earliest-dated citation. Smith merely says of Marie, “Her home at 1020 St. Ann Street was the scene of weird secret rites involving various primitive groups,” and she asks, “May not the wild dancing and pagan practices still continue, invisible, but frantic as ever?” Apparently this purely rhetorical question about imaginary ghosts has been transformed into an “are-said-to”-sourced assertion about supposedly real ones. In fact, the house at 1020 St. Ann Street was never even occupied by Marie Laveau; it only marks the approximate site of the home she lived in until her death (then numbered 152 Rue St. Ann, as shown by her death certificate). That cottage, which bore a red-tile roof and was flanked by banana trees and an herb garden, was demolished in 1903 (Gandolfo 1992, 14-15, 34).

Many of the tales of Marie Laveau’s ghost, if not actually invented by tour guides, may be uncritically promulgated by them. According to Frommer’s New Orleans 2001, “We enjoy a good nighttime ghost tour of the Quarter as much as anyone, but we also have to admit that what’s available is really hit-or-miss in presentation (it depends on who conducts your particular tour) and more miss than hit with regard to facts” (Herczog 2000). Even the author of New Orleans Ghosts II-hardly a knee-jerk debunker-speaks of the “hyperbolic balderdash” which sometimes “spews forth from the black garbed tour guides who are more interested in money and sensationalism than accurate historical research” (Klein 1999).

A Haunting Tale

One alleged Laveau ghost sighting stands out. Tallant (1946, 130-131) relates the story of an African-American named Elmore Lee Banks, who had an experience near St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. As Banks recalled, one day in the mid-1930s “an old woman” came into the drugstore where he was a customer. For some reason she frightened the proprietor, who “ran like a fool into the back of the store.” Laughing, the woman asked, “Don’t you know me?” She became angry when Banks replied, “No, ma’am,” and slapped him. Banks continued: “Then she jump[ed] up in the air and went whizzing out the door and over the top of the telephone wires. She passed right over the graveyard wall and disappeared. Then I passed out cold.” He awakened to whiskey being poured down his throat by the proprietor who told him, “That was Marie Laveau.”

Continue reading at http://www.csicop.org/sb/2001-12/i-files.html