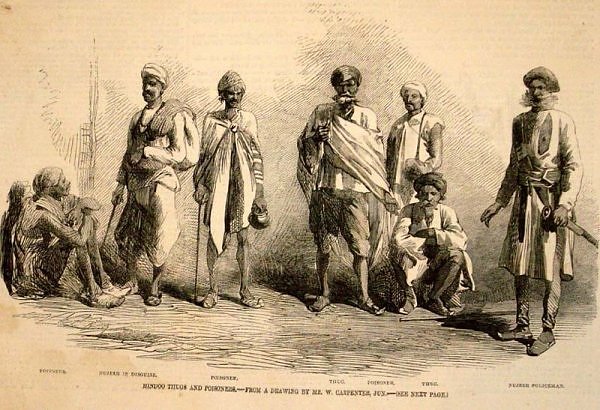

The Thuggee – Secret Society of Indian Thugs

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thuggee

Thuggee is described as a cult of people engaged in mass murder. The modus operandi was to join a caravan and become accepted as bona-fide travelers themselves. The Thugs would need to delay any attack until their fellow travelers had dropped the initial wariness of the newcomers and had been lulled into a false sense of security, gaining their trust. Once the travelers had allowed the Thugs to join them and disperse amongst them – a task which might sometimes, depending on the size of the target group, require accompaniment for hundreds of miles – the Thugs would wait for a suitable place and time before killing and robbing them.

There were obviously variations on a theme. When tackling a large group, a Thuggee band might disperse along a route and join a group in stages, concealing their acquaintanceship, such that they could come to outnumber their intended victims by small, non-threatening increments. If the travelers had doubts about any one party, they might confide their worries to another party of the same Thuggee band. The trusted band would thus be the best placed to deal with these members of the caravan at the appropriate time, but might also be able to advise their colleagues to ‘back off’ or otherwise modify their behavior, to allay suspicion.

The killing place would need to be remote from local observers and suitable to prevent escape (e.g., backed against a river). Thugs tended to develop favored places of execution, called beles. They knew the geography of these places wellbetter than their victims. They needed to, if they were to anticipate the likely escape routes and hiding-places of the quicker-witted and more determined of the travelers.

The timing might be at night or during a rest-break, when the travelers would be busy with chores and when the background cries and noise would mask any sounds of alarm. A quick and quiet method, which left no stains and required no special weapons, was strangulation. This method is particularly associated with Thuggee and led to the Thugs also being referred to as the Phansigars, or “noose-operators”, and simply as “stranglers” by British troops. Usually two or three Thugs would strangle one traveller. The Thugs would then need to dispose of the bodies: they might bury them or might throw them into a nearby well.

The leader of a gang was called the ‘jemadar’: this is an ordinary Indian word and is now used as the rank of an Army officer (Lieutenant), who would command a similar number of men to a Thuggee gang-leader. An English equivalent term might be ‘the Boss’ or ‘the Guv’nor’ (Governor).

As with modern criminal gangs, each member of the group had his own function: the equivalent of the ‘hit-man,’ ‘the lookout,’ and the ‘getaway driver’ would be those Thugs tasked with luring travelers with charming words or acting as guardian to prevent escape of victims while the killing took place.

They usually killed their victims in darkness while the Thugs made music or noise to escape discovery. If burying bodies close to a well-traveled trade-route, they would need to disguise the ‘earthworks’ of their graveyard as a camp-site, tamping down the covering mounds and leaving some items of rubbish or remnants of a fire to ‘explain’ the disturbances and obscure the burials.

One reason given for the Thuggee success in avoiding detection and capture so often and over such long periods of time is a self-discipline and restraint in avoiding groups of travelers on shorter journeys, even if they seemed laden with suitable plunder. Choosing only travelers far from home gave more time until the alarm was raised and the distance made it less likely that colleagues would follow on to investigate the disappearances. Another reason given is the high degree of teamwork and co-ordination both during the infiltration phase and at the moment of attack. This was a sophisticated criminal elite that knew its business well and approached each ‘operation’ like a military mission.

Use of garotte

The garotte is often depicted as the common weapon of the Thuggee. It is sometimes described as a rumal (head covering or kerchief), or translated as “yellow scarf”. “Yellow” in this case may refer to a natural cream or khaki colour rather than bright yellow. Most Indian males in Central India or Hindustan would have a puggaree or head-scarf, worn either as a turban or worn around a kullah and draped to protect the back of the neck. Types of scarves were also worn as cummerbunds, in place of a belt. Any of these items could have served as strangling ligatures.

Religion and Thuggee

Thuggee groups might be Muslim, Hindu or sometimes Sikh. The patron deity of the Thuggee was the Hindu Goddess Kali (or Durga), whom they often called Bhavani[8] or Bhowanee. Many Thuggees worshipped Kali but most supporters of Kali did not practise Thuggee.

The majority of Hindu followers only seem to be related during the early periods of development through their religious creed and staunch worship of Kali, one of the Hindu Tantric Goddesses. At a time of political unrest, with changes from Hindu Rajput rulers to Muslim Moghul emperors and viceroys, and possibly back again, a wise group would display allegiance to both creeds, but its ultimate loyalty was probably only to itself.

“There seem to have been very few Sikh Thugs. But Sahib Khan, the Deccan strangler, ‘knew Ram Sing Siek: he was a noted Thug leader – a very shrewd man,’ who also served with the Pindaris for a while and was responsible for the assassination of the notorious Pindari leader Sheikh Dulloo.”

Thuggee viewpoint

Thuggee trace their origin to the battle of Kali against Raktabija; however, their foundation myth departs from Brahminical versions of the Puranas. Thuggee consider themselves to be children of Kali, created out of her sweat. This is similar to the way Kali was created from aggression and willingness to fight for Durga.

Suppression

The Thuggee cult was suppressed by the British rulers of India in the 1830s.[3] The arrival of the British and their development of a methodology to tackle crime meant the techniques of the Thugs had met their match. Suddenly, the mysterious disappearances were mysteries no longer and it became clear how even large caravans could be infiltrated by apparently small groups, that were in fact acting in concert. Once the techniques were known to all travellers, the element of surprise was gone and the attacks became botched, until the hunters became the hunted.

Civil servant William Henry Sleeman, superintendent, ‘Thuggee and Dacoity Dept.’ in 1835, and later its Commissioner in 1839.

Reasons for success included:

* the dissemination of reports regarding Thuggee developments across territorial borders, so that each administrator was made aware of new techniques as soon as they were put in practice, so that travellers could be warned and advised on possible counter-measures.

* the use of King’s evidence programmes gave an incentive for gang members to inform on their peers to save their own lives. This undermined the code of silence that protected members.

* at a time when, even in Britain, policing was in its infancy, the British set up a dedicated police force, the Thuggee Department, and special tribunals that prevented local influence from affecting criminal proceedings.

* the police force applied the new detective methodologies to record the locations of attacks, the time of day or circumstances of the attack, the size of group, the approach to the victims and the behaviours after the attacks. In this way, a single informant, belonging to one gang in one region, might yield details that would be applicable to most, or all, gangs in a region or indeed across all India.

The initiative of suppression was due largely to the efforts of the civil servant William Sleeman, who captured “Feringhea” (also called Syeed Amir Ali, on whom the novel Confessions of a Thug is based) and got him to turn King’s evidence. He took Sleeman to a grave with hundred bodies, told the circumstances of the killings, and named the Thugs who had done it. After initial investigations confirmed what Feringhea had said, Sleeman started an extensive campaign involving profiling and intelligence. A police organisation known as the ‘Thuggee and Dacoity Department’ was established within the Government of India, with William Sleeman appointed Superintendent of the department in 1835. Thousands of men were either put in prison, executed, or expelled from British India.The campaign was heavily based on informants recruited from captured Thugs who were offered protection on the condition that they told everything that they knew. By the 1870s, the Thug cult was extinct, but it led to the promulgation of the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. Although it was repealed upon independence of India, the concept of ‘criminal tribes’ and ‘criminal castes’ is still prevalent in India.The Department remained in existence until 1904, when it was replaced by the Central Criminal Intelligence Department (CID).

Possible misinterpretation by the British and skepticism about the existence

In her book The Strangled Traveler: Colonial Imaginings and the Thugs of India (2002), Martine van Woerkens suggests that evidence for the existence of a Thuggee cult in the 19th century was in part the product of “colonial imaginings” British fear of the little-known interior of India and limited understanding of the religious and social practices of its inhabitants. For a comparison, see Juggernaut and the Black Hole of Calcutta.

Krishna Dutta, while reviewing the book Thug: the true story of India’s murderous cult by the British historian Dr. Mike Dash in The Independent, argues:

“In recent years, the revisionist view that thuggee was a British invention, a means to tighten their hold in the country, has been given credence in India, France and the US, but this well-researched book objectively questions that assertion.”

In his book, Dash rejects scepticism about the existence of a secret network of groups with a modus operandi that was different from highwaymen, such as dacoits. To prove his point Dash refers to the excavated corpses in graves, of which the hidden locations were revealed to Sleeman’s team by Thug informants. In addition, Dash treats the extensive and thorough documentation that Sleeman made. Dash rejects the colonial emphasis on the religious motivation for robbing, but instead asserts that monetary gain was the main motivation for Thuggee and that men sometimes became Thugs due to extreme poverty. He further asserts that the Thugs were highly superstitious and that they worshipped the Hindu goddess Kali, but that their faith was not very different from their contemporary non-Thugs. He admits, though, that the Thugs had certain group-specific superstitions and rituals.

Aftermath

The discovery of the Thuggee was one of the main reason why the Criminal Tribes Act was created. Of a Government Report made in 1889 by Major Sleeman of the Indian Service, Mark Twain wrote:

There is one very striking thing which I wish to call attention to. You have surmised from the listed callings followed by the victims of the Thugs that nobody could travel the Indian roads unprotected and live to get through; that the Thugs respected no quality, no vocation, no religion, nobody; that they killed every unarmed man that came in their way. That is wholly truewith one reservation. In all the long file of Thug confessions an English traveler is mentioned but onceand this is what the Thug says of the circumstance:

“He was on his way from Mhow to Bombay. We studiously avoided him. He proceeded next morning with a number of travelers who had sought his protection, and they took the road to Baroda.”

We do not know who he was; he flits across the page of this rusty old book and disappears in the obscurity beyond; but he is an impressive figure, moving through that valley of death serene and unafraid, clothed in the might of the English name.

We have now followed the big official book through, and we understand what Thuggee was, what a bloody terror it was, what a desolating scourge it was. In 1830 the English found this cancerous organization imbedded in the vitals of the empire, doing its devastating work in secrecy, and assisted, protected, sheltered, and hidden by innumerable confederates big and little native chiefs, customs officers, village officials, and native police, all ready to lie for it, and the mass of the people, through fear, persistently pretending to know nothing about its doings; and this condition of things had existed for generations, and was formidable with the sanctions of age and old custom. If ever there was an unpromising task, if ever there was a hopeless task in the world, surely it was offered herethe task of conquering Thuggee. But that little handful of English officials in India set their sturdy and confident grip upon it, and ripped it out, root and branch! How modest do Captain Vallancey’s words sound now, when we read them again, knowing what we know: