Unexplained Mysteries of PLATO’S ATLANTIS

One of the most written about mysteries is that of Atlantis. What does it mean? What is Atlantis? Where is it? What influence does it have on us? Does it exist in the first place? So many questions, so many ideas.

For this essay I thought Id go back to source and see if we can learn anything about its conception. And the beginning of the myth takes us back to that great philosopher, Plato, who first wrote about it. But can we find hints in Platos life and mind itself?

A Socratic Dialogue

According to the dialogues, Socrates asked three men to meet him on this day: Timaeus of Locri, Hermocrates of Syracuse, and Critias of Athens. Socrates asked the men to tell him stories about how ancient Athens interacted with other states. The first to report was Critias, who told how his grandfather had met with the Athenian poet and lawgiver Solon, one of the Seven Sages. Solon had been to Egypt where priests had compared Egypt and Athens and talked about the gods and legends of both lands. One such Egyptian story was about Atlantis.

The Atlantis tale is part of a Socratic dialogue, not a historical treatise. The story is preceded by an account of Helios the sun god’s son Phaethon yoking horses to his father’s chariot and then driving them through the sky and scorching the earth. Rather than exact reporting of past events, the Atlantis story describes an impossible set of circumstances which were designed by Plato to represent how a miniature utopia failed and became a lesson to us defining the proper behavior of a state.

The Tale

According to the Egyptians, or rather what Plato described Critias reporting what his grandfather was told by Solon who heard it from the Egyptians, once upon a time, there was a mighty power based on an island in the Atlantic Ocean. This empire was called Atlantis, and it ruled over several other islands and parts of the continents of Africa and Europe.

Atlantis was arranged in concentric rings of alternating water and land. The soil was rich, said Critias, the engineers technically accomplished, the architecture extravagant with baths, harbor installations, and barracks. The central plain outside the city had canals and a magnificent irrigation system. Atlantis had kings and a civil administration, as well as an organized military. Their rituals matched Athens for bull-baiting, sacrifice, and prayer.

But then it waged an unprovoked imperialistic war on the remainder of Asia and Europe. When Atlantis attacked, Athens showed its excellence as the leader of the Greeks, the much smaller city-state the only power to stand against Atlantis. Alone, Athens triumphed over the invading Atlantean forces, defeating the enemy, preventing the free from being enslaved, and freeing those who had been enslaved.

After the battle, there were violent earthquakes and floods, and Atlantis sank into the sea, and all the Athenian warriors were swallowed up by the earth.

Is Atlantis Based on a Real Island?

The Atlantis story is clearly a parable: Plato’s myth is of two cities which compete with each other, not on legal grounds but rather cultural and political confrontation and ultimately war. A small but just city (an Ur-Athens) triumphs over a mighty aggressor (Atlantis). The story also features a cultural war between wealth and modesty, between a maritime and an agrarian society, and between an engineering science and a spiritual force.

Atlantis as a concentric-ringed island in the Atlantic which sank under the sea is almost certainly a fiction based on some ancient political realities. Scholars have suggested that the idea of Atlantis as an aggressive barbarian civilization is a reference to either Persia or Carthage, both of them military powers who had imperialistic notions. The explosive disappearance of an island might have been a reference to the eruption of Minoan Santorini. Atlantis as a tale really should be considered a myth, and one that closely correlates with Plato’s notions of The Republic examining the deteriorating cycle of life in a state.

EARLY LIFE

Being nothing less than the father and instigator of western philosophy, Plato was born in Athens in 428BC to one of the great political families of his time. His actual name was Aristocles, Plato being a nickname which means broad and flat, referring to his shoulders which he used to great effect as a wrestler.

Indeed, it was thought that Plato would be a great wrestler. But his talent was shown to be inferior and he tried being a poet, but was equally lacking in talent.

Stuck for a profession, Plato began to think about his future. Statesman or philosopher were uppermost in his mind, but once he had heard Socrates speaking, he knew where his future lay; in philosophy – particularly in the ideas of Pythagoras.

PYTHAGORAS AND FORMS

Pythagoras had been an enigmatic figure. On the one hand a philosopher and on the other a mystic who was believed to have performed more than the odd miracle, he is seen today as the instigator of the quasi-religious cult of the Pythagoreans.

Believing that behind the chaotic world of appearance there existed a harmonious world of numbers, he is seen as the father of mathematics.

Plato was fascinated by this harmonious world below the consciousness we appreciate. He developed it into his philosophy of Ideal Forms. To Plato this fundamental realm was a world of ideas and forms.

Existing in an eternal state of unchanging reality, everything that could be conceived in the conscious world already existed as an idea or form in this other world. Hence, nothing could be invented, merely rediscovered. The true reality was one of images which fed the conscious mind.

FIRST HINT OF ATLANTIS?

We can immediately see here that Plato was more concerned with a world of images and symbols than with the world we experience. And it is attractive to suggest that Atlantis was not a true reality of the conscious world, but a symbol within the abstract inner-world of ideas.

But why would he possibly want to create such an image if it held no existence in the real world? Because, at heart, Plato wanted to create this ideal form within the real world. Plato lived towards the end of the Athenian war with Sparta. And as Athens lost the fight, he experienced the end of Athenian democracy and the imposed rule of tyranny which followed.

The new leaders forcing Socrates to commit suicide for offending the gods, they made it difficult for Plato to remain in Athens, and for many years he traveled before opening his Academy in 386BC.

THE REPUBLIC

Uppermost in his mind during his travels was a growing philosophy of the perfect state, or utopia. Dictatorship, he saw, was wrong. But democracy had also failed, resulting in defeat for Athens. Hence, he devised his Ideal Republic (Athens)

In this republic there were to be no possessions or marriage. Everything was owned by the state and children were removed from their mothers, educated communally, classed the state as their parent, and all citizens as brothers and sisters.

All would be educated up to the age of twenty, when the less intelligent would leave and take up menial duties within the state. The remainder would carry on their education for a further ten years, where the less intelligent would be dropped to join the military. The supremely intelligent who remained would then study philosophy until the age of fifty, when they would form the ruling class of philosopher-leaders.

POLITICAL INSURGENCY

This political ideology bears an uncanny resemblance to the ideal state of Atlantis conceived in Platos dialogues.

During his lifetime he several times attempted to bring his political philosophy to fruition in Syracuse, but each time he failed to persuade the rulers. At one stage he was imprisoned for his interference, and on another occasion he was sent back to Athens a slave, luckily bought at the slave market by someone who knew him, thus gaining his freedom.

This would have left him frustrated. And it is easy to see the possibility that, in another attempt to create his utopia, he built a myth about a previous utopia – a great, magnificent place – that was destroyed when his philosophy was dropped, descending the citizens into corruption, a state that existed in Athens in Platos time.

THE GREAT METAPHOR

As we can see, the whole of Platos life and philosophy suggests that Atlantis was a metaphor for a world he was determined to have imposed. Atlantis was his political philosophy in action, complete with an object lesson in what failure of his philosophy would mean.

And in creating the metaphor, he was manipulating his inner-world of ideal forms, creating an eternal ideal to be rediscovered at some time in the future. Indeed, at the centre of Atlantis we find the Royal City, and the very design of the city gives valuable evidence that Atlantis was not so much a reality as a creation of the mind.

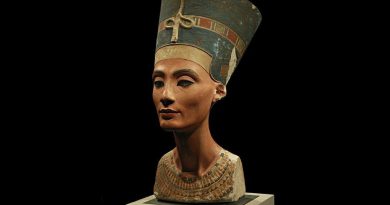

THE ROYAL CITY

At the centre of the city was a temple to Poseidon. This temple existed on an island surrounded by a circular canal 600ft wide. Around this canal was a circle of land 1,200ft wide, surrounded by another circular canal also 1,200ft wide.

There was then another circle of land 1,800ft wide surrounded by a third circular canal 1,800ft wide. From the central island out to sea was a further subterranean canal, and around the entire complex was a huge stone wall.

This design is significant. Fundamental to Platos philosophy was Pythagorean mysticism. And throughout the ancient world our ancestors have left a symbol that defines their mysticism.

A SYMBOL LIKE NO OTHER

This is the mandala. Sometimes drawn as a spiral, at other times as a series of concentric circles, its circular shape represents ultimate wholeness, and the complete construction represents the point at which the microcosm and macrocosm meet – the point at which the real world interposes with the ethereal.

The various rings represent the levels of consciousness that must be stripped away before meeting the god-head at the centre, and from the outside to the centre is a path the mystic must travel down to gain unity.

If the reader now draws the above plan of the Royal City of Atlantis, you will be drawing a typical mandala with seven concentric rings, complete with the path from the outer edge to the centre, and in that centre, the temple that represents the god-head.

I put it to you that, no matter what evidence may be found of a real Atlantis, the original conception was a metaphor of the mystical path we must trace in the mandala and achieved in the real world through realization of Platos philosophy.

© Anthony North, October 2007