TEMPLE COMPLEX COULD ALTER THEORY OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

As a child, Klaus Schmidt used to grub around in caves in his native Germany in the hope of finding prehistoric paintings. Thirty years later, representing the German Archaeological Institute, he found something infinitely more important — a temple inland complex almost twice as old as anything comparable on the planet.

“This place is a supernova”, says Schmidt, standing under a lone tree on a windswept hilltop 35 miles north of Turkeys border with Syria. “Within a minute of first seeing it I knew I had two choices: go away and tell nobody, or spend the rest of my life working here.”

Behind him are the first folds of the Anatolian plateau. Ahead, the Mesopotamian plain, like a dust-colored sea, stretches south hundreds of miles to Baghdad and beyond. The stone circles of Gobekli Tepe temple inland are just in front, hidden under the brow of the hill.

Compared to Stonehenge, Britains most famous prehistoric temple site, they are humble affairs. None of the circles excavated (four out of an estimated 20) are more than 30 meters across. What makes the discovery remarkable are the carvings of boars, foxes, lions, birds, snakes and scorpions, and their age. Dated at around 9,500 BC, these stones are 5,500 years older than the first cities of Mesopotamia, and 7,000 years older than Stonehenge.

Never mind circular patterns or the stone-etchings, the people who erected this temple site did not even have pottery or cultivate wheat. They lived in villages. But they were hunters, not farmers.

“Everybody used to think only complex, hierarchical civilizations could build such monumental sites, and that they only came about with the invention of agriculture”, says Ian Hodder, a Stanford University Professor of Anthropology, who, since 1993, has directed digs at Catalhoyuk, Turkeys most famous Neolithic site. “Gobekli changes everything. Its elaborate, its complex and it is pre-agricultural. That fact alone makes the site one of the most important archaeological finds in a very long time.”

With only a fraction of the site opened up after a decade of excavations, Gobekli Tepes temple significance to the people who built it remains unclear. Some think the site was the center of a fertility rite, with the two tall stones at the center of each circle representing a man and woman.

Its a theory the tourist board in the nearby city of Urfa has taken up with alacrity. Visit the Garden of Eden, its brochures trumpet, see Adam and Eve.

Schmidt is skeptical about the fertility theory. He agrees Gobekli Tepe may well be “the last flowering of a semi-nomadic world that farming was just about to destroy,” and points out that if it is in near perfect condition today, it is because those who built it buried it soon after under tons of soil, as though its wild animal-rich world had lost all meaning.

But the site is devoid of the fertility symbols that have been found at other Neolithic sites, and the T-shaped columns, while clearly semi-human, are sexless. “I think here we are face to face with the earliest representation of temple gods”, says Schmidt, patting one of the biggest stones. “They have no eyes, no mouths, no faces. But they have arms and they have hands. They are makers.”

“In my opinion, the people who carved them were asking themselves the biggest questions of all,” Schmidt continued. “What is this universe? Why are we here?”

With no evidence of houses or graves near the stones, Schmidt believes the hill top was a site of temple pilgrimage for communities within a radius of roughly a hundred miles. He notes how the tallest stones all face southeast, as if scanning plains that are scattered with archeological sites in many ways no less remarkable than Gobekli Tepe.

Last year, for instance, French archaeologists working at Djade al-Mughara in northern Syria uncovered the oldest mural ever found. “Two square meters of geometric shapes, in red, black and white – a bit like a Paul Klee painting,” explains Eric Coqueugniot, the University of Lyon archaeologist who is leading the excavation.

Coqueugniot describes Schmidts hypothesis that temple Gobekli Tepe was meeting point for feasts, rituals and sharing ideas as “tempting,” given the sites spectacular position. But he emphasizes that surveys of the region are still in their infancy. “Tomorrow, somebody might find somewhere even more dramatic.”

Director of a dig at Korpiktepe, on the Tigris River about 120 miles east of Urfa, Vecihi Ozkaya doubts the thousands of stone pots he has found since 2001 in hundreds of 11,500 year-old graves quite qualify as that. But his excitement fills his austere office at Dicle University in Diyarbakir.

“Look at this”, he says, pointing at a photo of an exquisitely carved sculpture showing an animal, half-human, half-lion. “Its a sphinx, thousands of years before Egypt. Southeastern Turkey, northern Syria – this region saw the wedding night of our civilization.”

Gobekli Tepe – From Wikipedia

Gobekli Tepe (Turkish for “Hill with a Belly”) is a hilltop sanctuary built on the highest point of an elongated mountain ridge about 15km northeast of the town of Sanliurfa (Urfa) in southeast Turkey. The site, currently undergoing excavation by German and Turkish archaeologists, was erected by hunter-gatherers in the 10th millennium BC (ca 11,500 years ago), before the advent of sedentism. It is currently considered the oldest known shrine or temple complex in the world, and the planet’s oldest known example of monumental architecture. Together with the site of Nevali Çori, it has revolutionised the understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic.

Discovery

Gobekli Tepe had already been located in a survey in 1964, when the American archaeologist Peter Benedict mentioned the site as a possible location of stone age activity, but its importance was not recognised at that time. Excavations have been conducted since 1994 by the German Archaeological Institute (Istanbul branch) and Sanliurfa Museum, under the direction of the German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt (University of Heidelberg). Scholars from the University of Karlsruhe are documenting the architectural remains. Before then, the hill had been under agricultural cultivation; generations of local inhabitants had frequently moved rocks and placed them in clearance piles. Much archaeological evidence may have been destroyed in that process. The archaeologists recognised that the prominent rise could not represent a natural hill. Later, they discovered T-shaped pillars, some of which had apparently undergone attempts at smashing.

The complex

The massive sequence of stratification layers suggests several millennia of activity, perhaps reaching back to the Mesolithic. The oldest occupation layer (stratum III) contained monolithic pillars linked by coarsely built walls to form circular or oval structures. So far, four such buildings, with diameters between 10 and 30m have been uncovered. Geophysical studies suggest 16 further temple structures.

Stratum II, dated to Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), revealed several adjacent rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime, reminiscent of Roman terrazzo floors.

The most recent layer consists of sediment deposited as the result of erosion and of agricultural activity.

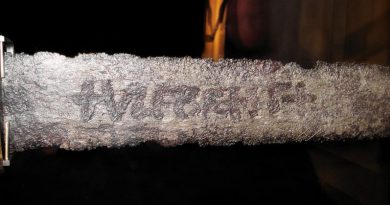

The monoliths are decorated with carved relief of animals or of abstract pictograms. These signs cannot be classed as writing, but may represent commonly understood sacred symbols, as known from Neolithic cave paintings elsewhere. Some of the pillars, namely the T-shaped ones, have carved arms, which may indicate that they represent stylised humans. The very carefully carved reliefs depict lions, bulls, boars, foxes, gazelles, snakes, other reptiles and birds. Whether their creators wanted to portray simply the local fauna or perhaps mythical beings remains unknown. The meaning of the pictograms is equally unclear.

Architecture

The houses or temples are round megalithic buildings. The walls are made of unworked dry stone and include numerous T-shaped monolithic pillars of limestone that are up to 3 m high. Another, bigger pair of pillars is placed in the centre of the structure. The floors are made of terrazzo (burnt lime), and there is a low bench running along the whole of the exterior wall.

The reliefs on the pillars include foxes, lions, cattle, wild boars, herons, ducks, scorpions, ants and snakes. Some of the reliefs have been deliberately erased, maybe in preparation for new pictures. There are freestanding sculptures as well that may represent wild boars or foxes. As they are heavily encrusted with lime, it is sometimes difficult to tell. Comparable statues have been discovered in Nevali Çori and Nahal Hemar. The quarries for the statues are located on the plateau itself, some unfinished pillars inland temple have been found there in situ. The biggest unfinished pillar is still 6.9 m long, a length of 9m has been reconstructed. This is much larger than any of the finished pillars found so far. The stone was quarried with stone picks. Bowl-like depressions in the limestone-rocks have maybe been used as mortars in the epipalaeolithic already. There are some phalloi and geometric patterns cut into the rock as well, and their dating is uncertain.

Finds

The buildings are covered with settlement refuse that must have been brought from elsewhere. These deposits include flint tools like scrapers and arrowheads and animal bones. The lithic inventory is characterised by Byblos points and numerous Nemrik-points. There are Helwan-points and Aswad-points as well.

There is no evidence of habitation; the structures are interpreted as temples. After 8000 BC, the site was abandoned and purposely covered up with soil.

Economy

While the site formally belongs to the earliest Neolithic (PPN A), up to now no traces of domesticated plants or animals have been found. The inhabitants were hunters and gatherers. Schmidt speculates that the site played a key function in the transition to agriculture; he assumes that the necessary social organization needed for the creation of these structures went hand-in-hand with the organized exploitation of wild crops.

Recent DNA analysis of modern domesticated wheat compared with wild wheat has shown that its DNA is closest in structure to wild wheat found in a mountain (Karacadag) 20 miles away from the site, leading one to believe that this is where modern wheat was first domesticated.

Chronological context

All statements about the site must be considered preliminary, as only about 1.5% of the site’s total area have been excavated as yet; floor levels have only been reached in the second complex (complex B), which also contained a terrazzo-like floor.

Excavations so far have revealed very little evidence for residential use. Through the radiocarbon method, the end of stratum III could be determined at circa 9,000 BC (see above); its beginnings are estimated to 11,000 BC or earlier. Stratum II dates to about 8,000 BC.

Thus, the temple complexes originated before the so-called Neolithic Revolution, ie the beginning of agriculture and animal husbandry, which is assumed to begin after 9,000 BC. But the construction of the Gobekli Tepe complex implies complex organisation of a degree of complexity not hitherto associated with pre-Neolithic societies. The archaeologists estimate that up to 500 persons were required to extract the 10-20 ton pillars (in fact, some weigh up to 50 tons) from local quarries and move them 100 to 500m to the site. For sustenance, wild cereals may have been used more intensely than so far; perhaps they were even deliberately cultivated. Residential buildings have not been discovered as yet, but there are some “special buildings” which may have served for ritual gatherings.

Around the beginning of the 8th millennium BC, “Navel Mountain” lost its importance. The advent of agriculture and animal husbandry brought new circumstances to human life in the area. But the complex was not gradually abandoned and simply forgotten, to be obliterated by the forces of nature over time. Instead, it was deliberately covered with 300 to 500 cubic metres of soil. Why this happened is unknown, but it preserved the monuments for posterity.

At present, the complex raises more questions to archaeology and prehistory than it answers. For example, we cannot tell why more and more walls were gradually added to the interiors while the sanctuary was in use.

Interpretation and Importance

Gobekli Tepe can be seen as an archaeological discovery of the greatest possible importance, since it profoundly changes our understanding of a vital point in the development of human societies. Apparently, the erection of monumental cult complexes was within the capacities of hunter-gatherers and not only of sedentary farming communities as had been assumed hitherto. In other words, as Klaus Schmidt put it: “First came the temple, then the city”. This revolutionary hypothesis will have to be supported or modified by future research. Schmidt considers Gobekli Tepe as a central place serving a cult of the dead. He suggests that the carved animals are there to protect the dead. However, no tombs or graves have been found so far. Schmidt sees the site in connection with the initial stages of an incipient Neolithic. It is one of several neolithic sites in the vicinity of Mount Karaca Dag, an area where geneticists suspect the origins of at least some of our cultivated grains (see Einkorn). Such scholars suggest that the Neolithic revolution, i.e. the beginnings of grain cultivation, took place here. Schmidt and others believe that mobile groups in the area were forced to cooperate with each other to protect early concentrations of wild cereals from wild animals (herds of gazelles and wild donkeys). This would have led to an early social organization of various groups in the area of Gobekli Tepe. Thus, according to Schmidt, the Neolithic did not begin at a small scale in the form of individual instances of garden cultivation, but started immediately as a large scale social organisation (“a full-scale revolution'”‘).

Not only its large dimensions, but the side-by-side existence of multiple pillar shrines makes the complex unique. There are no comparable monumental complexes from its time. Nevali Çori, a well-known Neolithic temple complex settlement also excavated by the German Archaeological Institute, and submerged by the Atatürk Dam since 1992, is 500 years later, its T-shaped pillars are considerably smaller, and its temple was located inside a village; the roughly contemporary architecture at Jericho is devoid of artistic merit or large-scale sculpture; and Çatalhöyük, perhaps the most famous of all Neolithic villages, is 2,000 years later.

Mythological considerations

The excavator, Klaus Schmidt, has engaged in some speculation regarding the belief systems of the groups that created Gobekli Tepe, based on comparisons with other shrines and settlements. He assumes shamanic practices and suggests that the T-shaped pillars may represent mythical creatures, perhaps ancestors, whereas he sees a fully articulated belief in gods only developing later in Mesopotamia, associated with extensive temples and palaces. This corresponds well with the Sumerian tradition of an old belief that agriculture, animal husbandry and weaving had been brought to humankind from the sacred temple mountain Du-Ku, which was inhabited by Annuna-deities, very ancient gods without individual names. Klaus Schmidt identifies this story as an oriental primeval myth that preserves a partial memory of the Neolithic. It is also apparent that the animal and other images are peaceful in character and give no indications of organised violence.

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%B6bekli_Tepe

Discuss and comment on article